Malt Conditioning Exploration

This is a minor revision and edit of the article published in 2017.

Malt Conditioning is one of those techniques that many home brewers explore, but may not understand. In my efforts to reduce HSA and LO2, conditioning malt is recommended, as it allows one to finely crush malts while causing less overall damage to the barley husks and acrospires. Since I brew with a circulated mash, efforts to retain intact husks and reduce flour improve mash bed flow. It also allows me to mill much finer than I would with a purely dry method. However, I have noticed some inconsistency in extract efficiency over my past several brews. Conditioning malt before milling should allow me to maximize extract efficiency with circulation and produce a good lauter.

Discussion

Kunze (Technology Brewing and Malting, 3.1.3.6) describes this as "conditioned dry milling," and it is the most approachable technique available to home brewers. After gathering the grist recipe, you take 1%-2% by weight of hot water and heat it to around 90° C/194° F. I use DI or RO water and boil it in my tea kettle. Kunze recommends 30-35 °C; however, I find that hotter water yields fluffier husks. This is weighed out into a measuring cup and then poured over the malt. Then stir and stir.

In this article, Kai Troester describes conditioned malt as leathery. Stirring the malt with water should allow the husk to absorb moisture. The texture shifts from a papery, rough feel to a more leathery one. You should stir until the malt no longer feels wet or damp. I like to let this rest for 5-10 minutes, then stir a final time. With large grain bills, I will pour this back and forth between Homer buckets. Once the malt feels dry to the touch, it is ready to mill. It is possible to do this a day before and let it rest.

One can also use a spray bottle, but the measurement becomes more difficult. Marking the side of a bottle and adding the required volume above that mark lets you spray until you reach the mark. However, a 90 °C temperature may make the spray bottle uncomfortable to hold. Steam is another possibility that Chris Colby contemplates in this article. I am not convinced that the water temperature makes much difference, aside from the apparent "fluffier" husk quality. I simply use "warm" water.

The goal is to raise the overall moisture level from the normal 2%-4% (which allows the malt to be stored without spoiling) to roughly 0.7% higher. The husk takes up most of the moisture, while the interior of the barley remains very dry. When milled, the husk remains resilient, and the mill's shearing allows it to come free, more or less intact. The endosperm can be split and cracked into grits.

There has been some discussion about using conditioning to reduce both lipoxidase and peroxidase, enzymes implicated in beer staling. It seems unlikely that we would see much benefit here; however, Kunze also discusses the goal of leaving intact husk and acrospires, the primary sources of these enzymes, which should reduce the mash's oxidation potential. As shredded husks can release polyphenols and silica, whole husks should reduce the risks of tannin extraction and astringency.

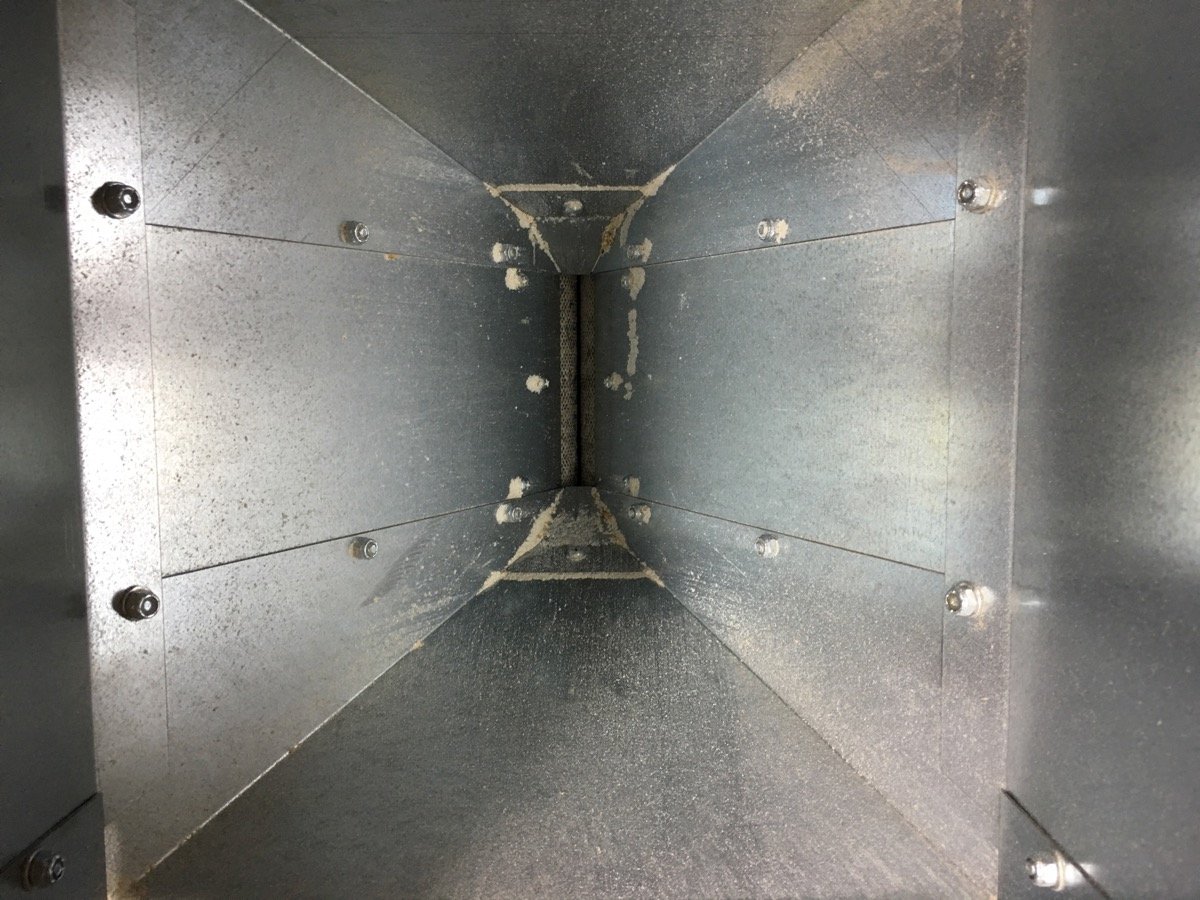

The biggest downside is the potential mess left on the mill, with flour dough caking up on the rollers. I have found that both letting the malt rest before milling and reserving a small portion of the dry malt to run after the conditioned portion help minimize this buildup. A wire brush used during your normal maintenance can knock off anything that remains.

The Experiment

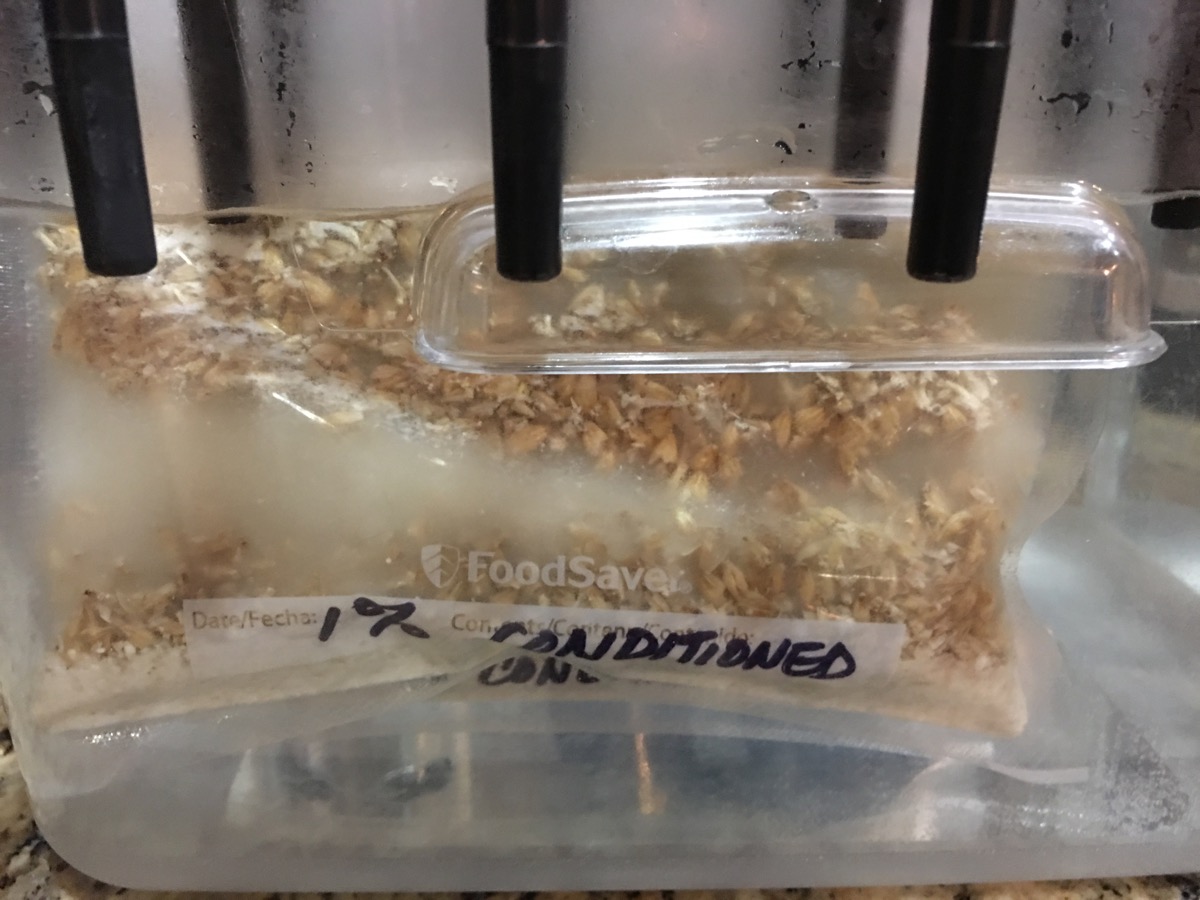

Because I was seeing some issues, I decided to run a test to see if the water content in conditioning has a measurable impact. Emulating a congress mash, three 50-gram samples were collected. The control was dry malt, and the other samples were treated with either 1% or 2% water by weight. Conditioning occurred in bags, dosing the first sample with a mere 0.5 grams of 90 °C water. The second sample was dosed with 1 g of water at 90 °C. The malt and water were shaken thoroughly and then left to rest for 10 minutes.

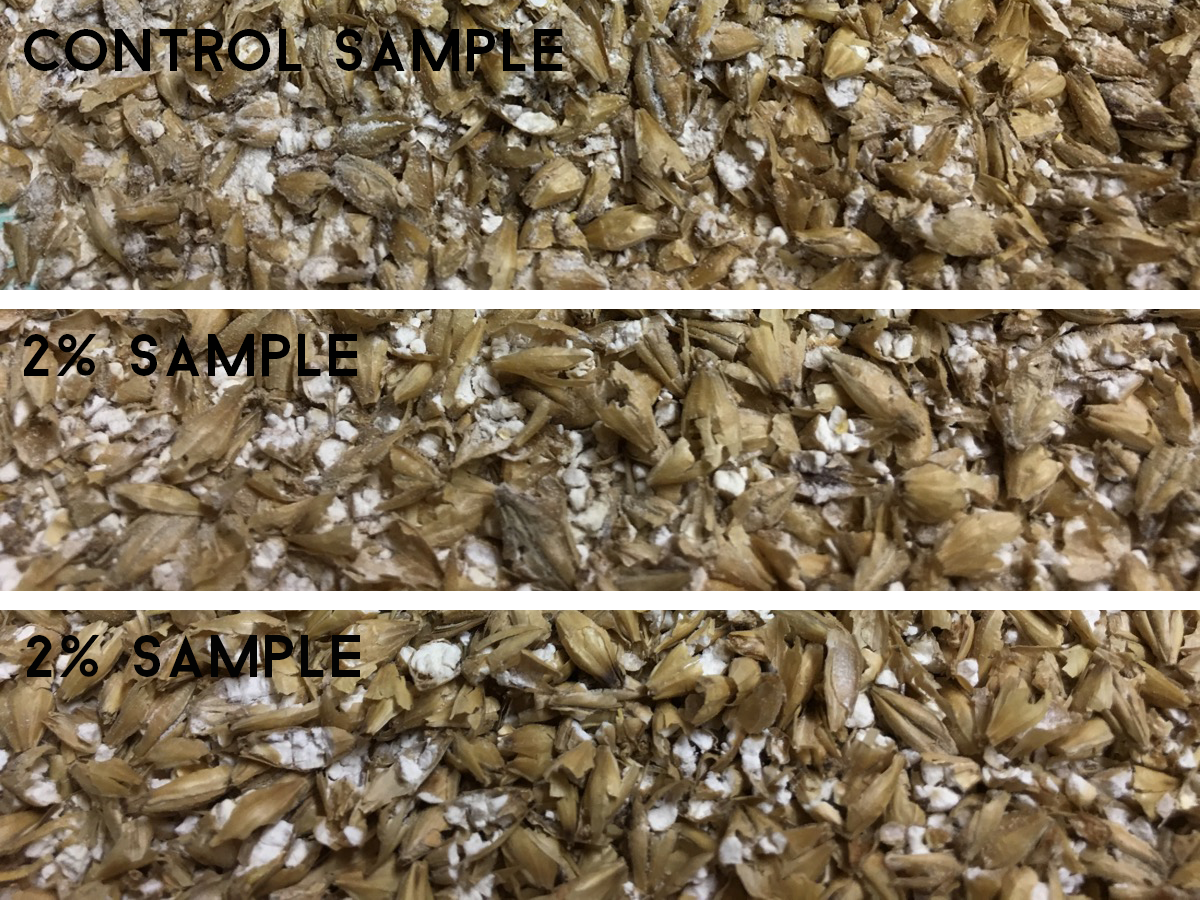

- Dry Malt - was papery and rough; a large fraction of flour, lightly shredded husks

- 1% Conditioned - slightly leathery, less rough; smaller fraction of flour, intact husks, nice grit size

- 2% Conditioned - soft leather feel, no roughness, minimal flour; fluffy husks, larger grits than 1%

Each sample was then milled on my Monster Mill MM-3Pro, with a 0.022" gap. The mill is powered by an All-American Ale Works 180-RPM electric motor, with direct drive via Lovejoy couplers. I built this setup about two years ago, and the motor has removed some inconsistencies in my milling. The small samples were collected onto a paper plate.

Each sample was then returned to its assigned bag, and 200 ml of DI water was added. These were then placed in a sous vide bath and ramped to 154 °F, held for an hour, then ramped to 170 °F for 10 minutes. The bags were clipped together on a rack, and I would occasionally agitate the bag assembly.

Each bag was then drained through a strainer and a coffee filter. The wort was collected and measured for final pH, volume yield, and extract.

Results

- Control: 139 ml volume, 5.81 pH, 15.2 brix or 1.062 gravity

- 1% Sample: 142 ml volume, 5.82 pH, 15.2 brix or 1.062 gravity

- 2% Sample: 146 ml volume, 5.82 pH, 11.9 brix or 1.048 gravity

The results are baffling. While pH is very consistent, there is a small trend of increased lauter efficiency. Samples were drained completely, but not squeezed. While this is not a perfect procedure, all samples were allowed to fully drain through a cut corner in the bag.

The strange thing was the lack of extract efficiency in the 2% sample. The control and the 1% were identical. These measurements were made using an electronic refractometer, which was cleaned and zeroed between measurements with DI water. I triple checked the measurements and the 2% sample.

I generally get better mash performance when I condition malt. Is it absolutely necessary? Probably not, but when using a recirculation-style mash, it helps to use larger husks to facilitate flow, and I have had fewer stuck sparges since making this a regular part of my brew day. Does it help with LO2 brewing? Maybe, but that would likely require sacrificing a batch without using the O2 scavengers in the mash and taking measurements. I did this early on, and it's not clear that there is a measurable effect, at least with my DO meter.