Improving Your Recipes

One of the more frustrating (or fun, depending on your perspective) challenges for a brewer is developing and establishing your own recipes. A great brewer's recipe creation skills sets a path for a successful brew; outlining procedure and visualizing the beer in the glass. Every brewer seems to have their own dogmatic approach, but don't get caught between a rock and a hard place. Learn to adapt the recipe to your style and system.

Here are some universal concepts that can guide you to successful recipe creation and it all starts with the basics.

Use the freshest possible quality ingredients.

I am astonished by the number of folk that buy massive amounts of grain and hops, and store them for years in a hot garage. Remember that malts and hops are perishable. I think most people understand that hops should be stored under vacuum and in a freezer, but forget those bags of malt in the garage are subjected to large changes in temperature and humidity. It is important to store them in a cool dry place, and in a way that minimizes rodent activity. Plastic dog food containers can be found in sizes that hold an entire bag of base malt and seal air tight. For smaller volumes, I like to vacuum bag in common weights (1 lb - 2 lb) I use in my recipes. These may be stored in a fridge, but I tend to use buckets with sealing Gamma lids without refridgeration. Storing in buckets also allows me to sort things and keep them handy, and at least attempt to protect them from light, large temperature and humidity swings. If you must buy crushed grains, store cold and it should keep for a while. Generally, I try not to use grains past 6 months and I believe I can taste the difference.

If you are not using the malts immediately, it is a good idea to freeze the malt to kill weevils. I have upright freezers for fermenting - so when one is free, I can stack about 3 bags of malt and let them freeze for a few days. It is important that these return to room temperature in a fairly dry place, or moisture can condense and cause spoilage and mold. Feel free to place vacuum packed malts in the freezer as the bags will prevent the moisture retention.

So some best practices:

- Plan ahead and buy your malts appropriately - the closer to the brew day the better. Use up your malts as quickly as possible to ensure freshness.

- Evaluate your malt at the LHBS and before you mill. It should smell and taste like malt, and be free from musty aromas and bug free.

- Buy from a store that has good turn over. If you are using an unusual malt, ask the proprietor how fresh it is. Make sure they understand you only want the freshest ingredients. If the hops are not stored in a chill chest - don't buy it.

- Buy branded malts when you can, especially with continental or British styles. Getting to know how a specific vendor's malt behaves and tastes will help you perfect your beer. Skip the generic malt at the LHBS for a special beer.

- Run test single malt batches. This helps you to better understand what the fermented malt tastes like in the glass. Develop a standard recipe for these so that you have some consistency, but also produce a drinkable beer. Using a very clean strain, ale or lager, let's you fully test the malt character.

- Learn about hop varietals, malt varietals, the processes used to package and find trusted vendors. Beware marketing terms that may confuse actual processing.

- Use fresh, vigorous and viable yeast. Use a proper starter. Ferment at the right temperatures. This has been beaten to death elsewhere, no need to rehash. Finally... use the yeast you think is appropriate for the style.

Find Trusted Resources.

Gordon Strong's new book, "Modern Homebrew Recipes: Exploring Styles and Contemporary Techniques" directly addresses one of my biggest frustrations with recipes; they almost never include detailed process and system descriptions. Gordon gives an amazing amount of detail. A recipe should always declare a base efficiency, mashing schedule and some information on the system used, even a rough idea of what mash pH was utilized or water profile targeted.

Choosing a good base recipe is critically important, as is awareness of the historic ingredients and processes. Recently, I have been looking at a variety of Maibock recipes. The variations on the theme run from 100% Vienna grists to complicated grists with Pilsner, Munich, Vienna and melanoiden. Hop bills from single Magnum at bittering to FWH with tremendous amounts of Tettnang and flavor and aroma additions later in the boil. One recipe is built from a respected German brewery, the other from an award winning homebrewer. It can be confusing, and failure can be frustrating.

Some thoughts on recipe evaluation:

- Simpler is better. There are fewer chances for an issue, with the caveat that processing and technique become more important. That said - there are styles that require a lot of complexity, but I tend to avoid recipes with more than 3-4 malts or more than 3 hops.

- Consider the source. Personally, I avoid the big recipe databases, unless I recognize the brewer and I can ask questions directly. Zainasheff and Palmer's "Brewing Classic Styles" is a great place to reference a specific style, and the recipes easily modified for a successful beer. Blogs, forums, homebrew club mates or online friends can also point you in the right direction. Also, take a look at the AHA recipe database for NHC medal winning recipes! But be skeptical of any recipe.

- Figure out how the recipe was originally brewed. If the recipe calls for dark malts at vorlauf, clarify the time they are in the mash. Or if it calls for a whirlpool or hopstand addition, make sure to understand the temperature of the wort and the time of hop contact. If you have such questions - reach out to the recipe creator and understand their procedures.

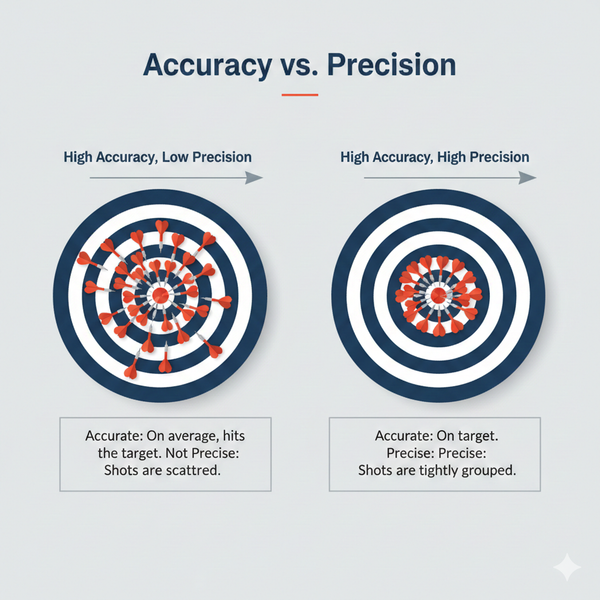

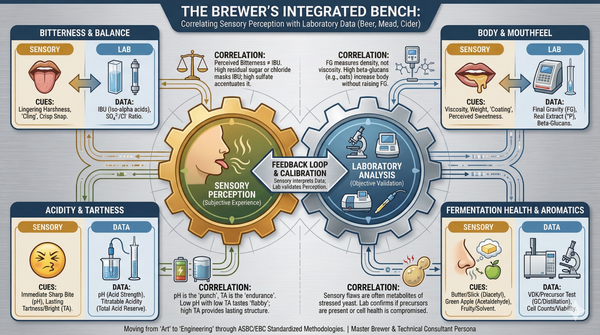

- Brew and conduct critical sensory testing, both personally and with a trusted experienced brewer. Entering these beers into competition may also help you calibrate small changes. Take the feedback seriously, when it is constructive. Ignore the haters. Drew and Denny go deep on this in "Experimental Homebrewing".

- Intentionally vary your recipe. Sometimes a small change or a significant 'risky' change can make magic. I recently brewed my favorite saison subbing a very large portion of flaked rye, rather than wheat malt. It may become my new favorite house saison.

Know Your Brewery.

I am most guilty of adding new gear (hopback, whirlpool arm, etc.) to my brewery and then getting frustrated when my results change (often for the worse). Typically, it takes me a few brews with a new item to really get a handle on it. Using the hopback, I have made big mistakes in expecting certain levels of bitterness, or expected far less bitterness with whirlpooling. Sometimes the results are surprisingly good, but often, it's disappointing. New gear can also be distracting - so you fiddle with something and let something else slide (at the least I do this...). Designing around a new piece of equipment really requires experience so you understand how a specific technique and equipment will impact the recipe.

Knowing your equipment, how it behaves, what efficiency you should expect (especially extract and brew house) gives you a solid platform to adapt and design your recipe. I have brewed just under 100 batches on my RIMS system. I have a consistent efficiency and a natural feeling for how it is going to work (even the system quirks). I also know that I need a very coarse crush and very fast circulation to establish that efficiency. I have a ritual for building my water, heating the strike and so forth. I can create a recipe and brew with extreme confidence that I can get my expected result, until I screw up. Still, it takes some planning and preparation, usually the evening before, to have a successful brew day.

If you know your system, building up an equipment profile for your favorite recipe software is simple. Brew a few times and look closely to analyze when some result is not as expected. You may need to calculate brew house losses from longer hoses, plate or counter flow chillers or unknown/unmeasured dead spaces. I had to go back through my entire system to discover that liquid measurements varied from device to device... so I re-calibrated volumes to match losses on my cold side. Some advice:

- Consider the impact any new equipment or technique will have on your system. Look at efficiency, volume losses or gains, and consider the implication on the recipe goals.

- Wet run new gear with water (cool) before you commit hot wort and a carefully crafted recipe. Make sure nothing is leaking and that you thoroughly understand the new procedure. Mark valves and hoses so you know what does what.

- Dial in your software through careful measurements through a number of brews. When you change something, modify your equipment profile OR duplicate it and make changes specific to your new configuration.

- Keep all your equipment clean and in good working order. Keep things as simple as possible and plan out your day.

Brew a Lot and Keep Great Notes.

Erk. (brakes squealing, tires smoke and glass breaks) This is my weak spot. I brew, I take notes and never transcribe them into the computer. Most of the time, the paper just gets tossed into the trash. Using brewing software is a horrible way to keep notes. I have started to transcribe my favorite personal recipes into a notebook. As I brew, I intend to keep this at hand (and somewhere I cannot splash wort or beer on it) to keep very detailed notes, all processes and steps, from liquor treatment all the way through packaging. Note where you submit beers for competition, and copy in the judging notes that are relevant.

Own It.

At the end of the day, own it. You are responsible for the grains, hops, water and yeast (and whatever else) makes it into the bottle (or keg). So put your recipe together and strike out for golden/amber/brown/black foamy glory. So regardless of your recipe theories, it is time to put fire to the kettle and brew. Don't veer from the plan (or at least document when you do). Last minute changes or judgement calls throw you off the plan and risk the brew. Brew the recipe several times refining it based on your preferences and constructive feedback. Care for it, nurture it. No excuses...

That recipe is yours now. It is common courtesy to give credit where it is due, especially if you didn't make a substantial change to it. And I encourage you to change things up a bit. I don't want to get into a debate over this. The recipe is simply a roadmap to making a good beer, and with identical recipes 4 different brewers will have 4 different beers, often very different. If I make a slight change to a recipe, it will be named the same as the original recipe and the source noted, even if entered into comps. If I make substantive changes, then I do no worry about it. Be open with your recipes and techniques without being egotistical. Generosity usually results in good friendships, respect and an occasional taste of some amazing brews.

Absolutely NOTHING replaces experience in brewing and being able replicate a happy accident or know what succeeded or failed in your recipe toolbox. Was the beer too dark? Did it have a wonderful toffee character? Did your fermentation therm controller fail and ramp the temp, but the beer was amazing? Your notes and journal will let you recreate that perfect beer, or at least give you something to laugh at later in your career!