High-Gravity ABV and the Precision Gap

A data-driven look at why standard ABV formulas fail in high-gravity fermentation and how to implement higher-precision models.

We’ve all been there. You hit a massive target $OG$ of $1.110$, the fermentation is vigorous, and it finishes at a clean $1.020$. You plug the numbers into a basic calculator, and it tells you you’ve hit $11.8%$. But something feels different. The warmth, the mouthfeel, and the sheer "bigness" of the mead or beer suggest more.

The truth is, your calculator is likely lying to you. It’s using simplified math, rather than accomodating for complex ethanol to water relationships.

Most of us, with experience, understand this. However, it is a good reminder to check your tools, your process, and how you apply precision to your batch logs.

The Tools: Resolution vs. Reality

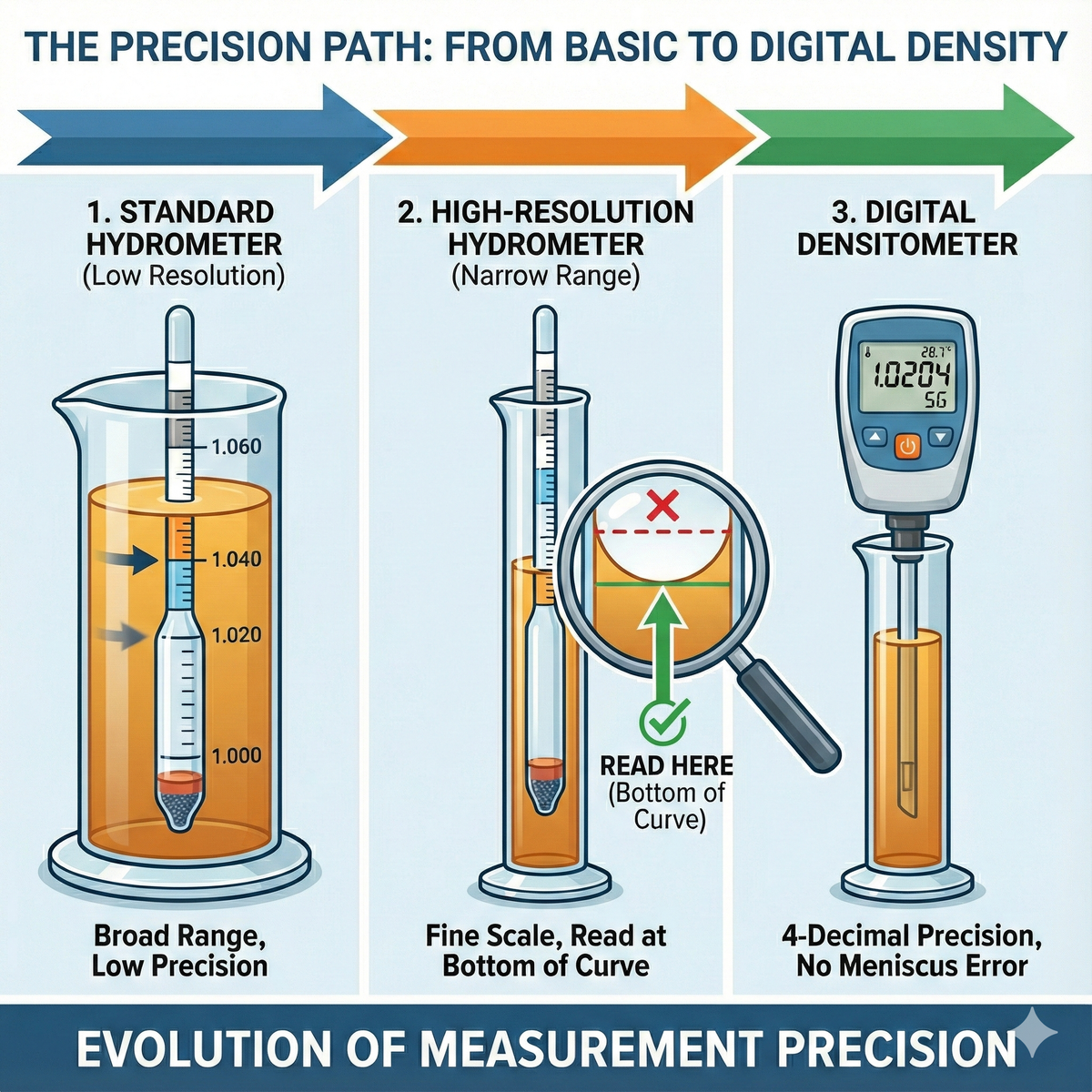

To move toward Lab-First precision, we must address hardware options.

1. High-Resolution Hydrometers

Standard hydrometers cover a massive range (e.g., $0.990$ to $1.170$). According to ASBC Method Beer-2 (Specific Gravity), precision in measurement is the foundation of all brewery calculations. High-resolution sets (narrow range) allow you to see $0.5$ point differences that standard units miss.

The price differences here are easily 2X the cost of a standard hydrometer, but you also tend to get a higher quality construction that will last longer. As always, treat these with extreme care as they are fragile, and the reference papers can slip. It's always a good idea to periodically check calibration in temperature standard distilled water to ensure a precise reading at 1.000.

Temperature and gassiness of the sample play a role. You should always measure at a standard temperature (20C or 68F for ASBC, 60F for NIST - use the vendor recommendations) and use a degassed and filtered sample to remove excess break and hop materials. Gently lower the hydrometer into the sample and give it a little spin to release any residual bubbles. Let this settle for a minute and take a reading. Always document both the temperature, reading and note turbidity in your log.

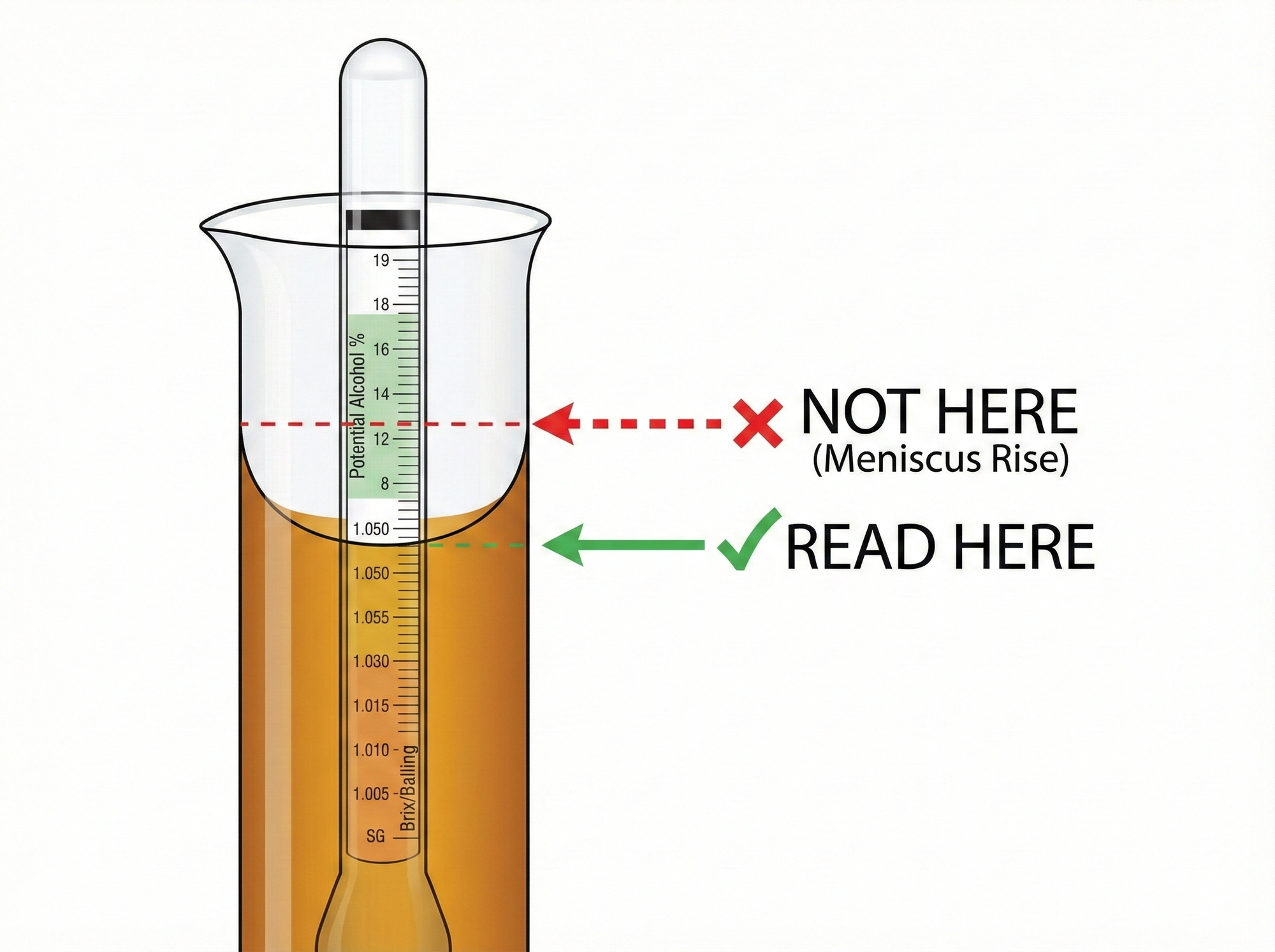

2. The Meniscus: The Human Error Factor

Always read at the absolute bottom of the curve at eye level when using an analogue hydrometer. If you read the top of the "climb," you are consistently over-reporting your $FG$, which artificially lowers your calculated ABV.

3. Digital Densitometers

As noted in MBAA Technical Quarterly (Vol. 51), digital densitometry (like the Anton Paar EasyDens) provides a level of telemetry that makes the "One-Change Rule" actually possible to track by providing four decimal places of accuracy ($0.0001$). This is a substantial cost, and you need to decide if this is a must-have. In a commercial setting, this should be a must have for your lab, or a more complete analytic appliance that can do even more.

Having a specific and repeatable reference temperature avoids damage to the device and over-reliance on digital Automatic Temperature Correction (ATC) which is designed to compensate for minor temperature differences. Never use hot wort. This is also true for pH meters and measurements.

4. Digital Refractometers

It should be noted that analogue refractometers are particularly difficult to use with precision. There are many factors that come into play, and they are really designed as field tools to measuring approximate sugar concentrations in fruit or other solutions. Digital Refractometers help to reduce error, and are useful for spot checks, especially as a second potential gravity measurement. The Anton Paar SmarRef, when paired with their densitometer is a powerful alalytical tool, however comes with an annual subscription to use in combination. As the costs ($$$) and the algorithms are quite different, I'll move along.

The Math: Linear vs. Non-Linear Models

While most brewing software handles the heavy lifting, understanding the relationship between measurement scales is fundamental for process control. Specific Gravity (SG) is the industry standard for beer, measuring the density of the wort relative to pure water (1.000).

In contrast, Brix and Plato (°P) are mass-fraction scales used primarily in wine, cider, and commercial brewing to represent the percentage of sucrose by weight in a solution. For technical accuracy, these units are roughly related by the "Rule of Four," where $1°\text{P} \approx 4$ gravity points ($1.004$), though this relationship becomes non-linear at higher concentrations. Furthermore, digital tools like refractometers measure the Refractive Index (RI), which requires a specific correction factor once ethanol is present, as alcohol skews light refraction differently than sugar. We will proceed using Specific Gravity.

The standard formula we all memorized is a linear approximation:

$$ABV_{std} = (OG - FG) \times 131.25$$

However, ethanol is significantly less dense than water ($\approx 0.794 \ SG$ at $20°C$). For big ferments, we need the High-Precision Formula, popularized by researchers like Crouch (1995):

$$ABV_{alt} = \left[ \frac{76.08 \times (OG - FG)}{1.775 - OG} \right] \times \left( \frac{FG}{0.794} \right)$$

This equation accounts for the changing mass-to-volume relationship as the yeast turns heavy sugar into light spirit. While not perfect, it certainly resolves a more accurate sugar concentration. The tool below allows you to compare simple OG to FG and illustrates the delta potential between algorithms.

ABV Precision Lab

Why It Matters

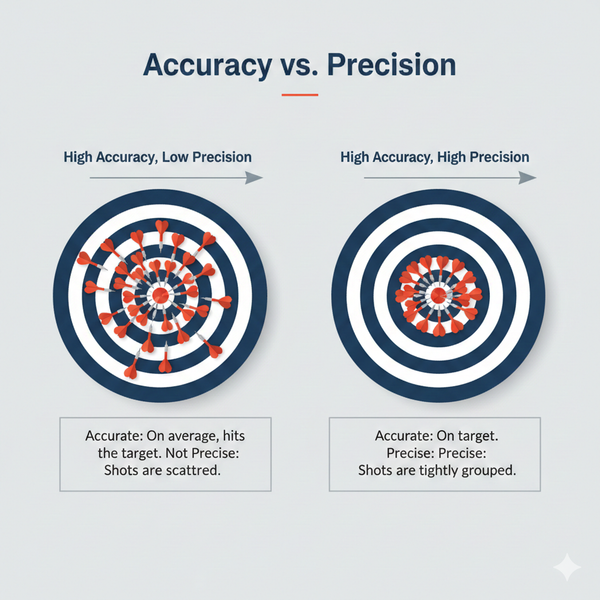

Precision isn't about being pedantic. It's about having the right map (and batch logging) so that when you finally achieve that "Lightning Strike" batch, you have the interpretative data needed to replicate it. When you are precice, you can calibrate for precision and you can adjust for accuracy (for a different post).

Each maker needs to decide what fits for their personal philosophy, finances, and goals. This is not an arms race, however, precision is within grasp if the brewer is able to plan, save, and have the discipline to log and interpret all measurements. Consistency is key, and having data to illustrate how even minute changes can affect the final product allows the maker to have confidence to create or recreate that award winning beverage.

Resources & Standards:

- ASBC Methods of Analysis: Method Beer-2 (Specific Gravity).

- MBAA Technical Quarterly: Volume 51, "Digital Densitometry in the Craft Brewery."

- Crouch, L. (1995): The Non-Linear Relationship of Wort Gravity to Ethanol Yield.

*Disclosure: AI (Gemini Pro 3, Thinking) was used to research this post, create illustrations and to enable Ghost Pro to show the LaTex notation for the math calculations. I have reviewed and confirmed facts using the references above and other resources. *