Brewing With a Master - Ricardo Fritzsche

Meet Ricardo

About a year and a half ago, I met this energetic dude with a strong Southern (that is Argentinian) accent, that was coming back to Austin after spending a few years in Munich. Ricardo engaged the Zealots, looking to get back involved. Even while shipping beers over from Germany, he was taking medals in the US. If you were at the AHA HomebrewCon (jeez I still can't say it), Ric and his lovely bride were bopping around the Zealot's booth in lederhosen.

Ricardo (Ric) and I have discussed low oxygen quite a bit, and it has been clear for a while that LO2 was already intrinsic to Ric's brewing philosophy. He has been Ric-Rolling through the 2016 Lone Star Circuit, most recently winning the individual category by a respectable 38 point lead. This is no small feat in a circuit that is front loaded with great brewers!

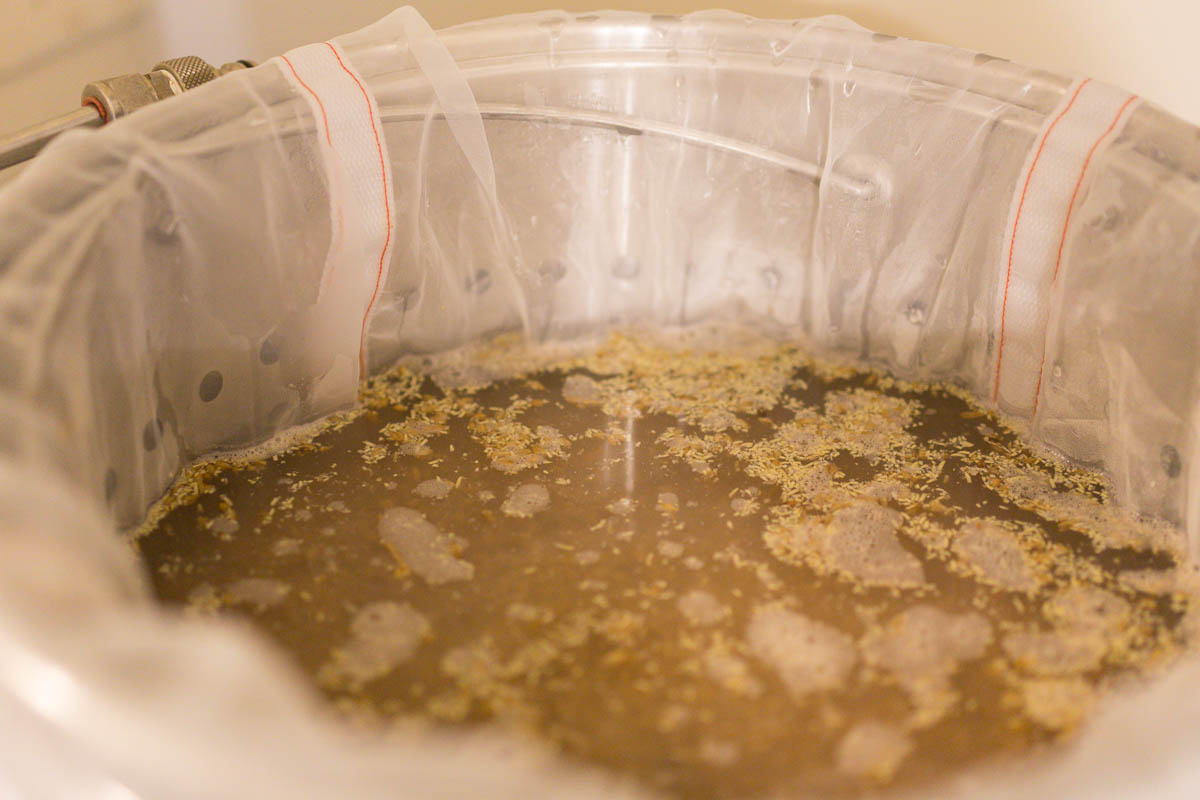

I got the opportunity to crash a recent brew day. Ric was experimenting with sugar and yeast to reduce DO in the mash water, rather than a preboil and metabisulfite addition before grain in. He simply added 11 grams of table sugar and 11 grams of dry yeast to the mash water, and held the temperature around 90F for 30-45 minutes. Then the mash was brought up to strike temperatures for grain in.

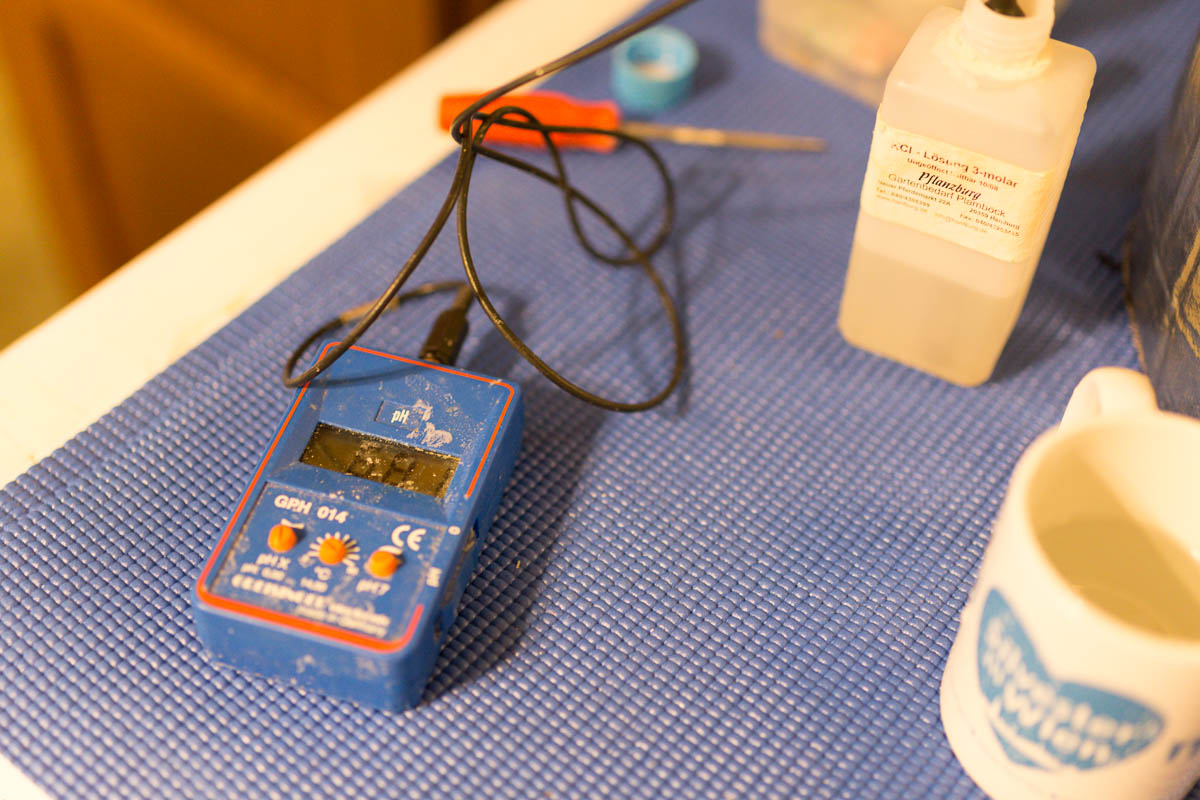

A very small amount of sodium metabisulfite, ascorbic acid, and BrewTan B was then used in the mash at grain in to scavenge any O2 uptake. Ricardo doesn't have a DO meter (and I forgot mine), but it appeared to work very well. There was very little (if any) darkening of the wort, and the cast wort was incredibly flavorful and delicate!

Q&A

(M) How did you get started in brewing?

(Ric) I have been a craft beer fan since a Grad School Happy hour at the late Waterloo Brewing Co (Austin, TX) in 1995. In 2007, a co-worker invited me to homebrew at his house (and take the beer with me). I chose the Austin Homebrew Supply's American Barley Wine in mini-mash form, went through the motions and bottle conditioned the beers in 33cc flip-tops. I remember the beers being pretty good (a bit fusel-y).

I was hooked after that. I started doing whole grain after moving to Munich in 2010.

Sidebar: An interesting detail is that I never force carbonated a beer in my life. All my beers have been bottle or keg conditioned.

(M) Having come from Argentina and Germany, what is your general impression of the US's homebrewing culture?

(Ric) I came to the US in 1991 for Graduate School, and although I returned for three years in 1999, I did not have much contact with homebrewers. The German homebrewing culture has a much longer tradition but has not experienced the exponential growth the American culture has had.

There are not as many homebrewers in Germany as there are in the US, but the level is very good. Most of them can and do brew lagers regularly. Another oddity is that the homebrewer group in Munich is at least 40-50% retired pro-brewers, most of them only drink/ like Munich beers (Helles, Dunkles, and an occasional Weizen or Bock).

(M) Describe your favorite meal and what beer to pair with it? (For the record, Ric's wife is a tremendous cook!)

(Ric) What about me??? Third place at recent Chili cookoff, not too bad! Back to the question, my favorite pairings are those that enhance both the food and the beer. I love a good dry IPA (Pliny-like) with sweets like carrot cake; I also like Goulash (enter your favorite chili here) and Schlenkerla smoked doppelbock. Munich Helles goes well with light food, bread, and even fish or chicken if not heavily spiced. For pork and beef, a Märzen, Dunkel, Dunkelweizen or Bock.

(M) What is your position on low oxygen brewing?

(Ric) On the hot side, the scientific data shows a benefit for flavorful, light lagers (eg Munich Helles). The data is not validated at the homebrew scale but given the potential for oxidation is much higher at our scale, I think that good homebrew research is likely to show a difference in light, flavorful lagers. There is no data on other styles, and I think if any differences exist, will be much more difficult to prove.

On the cold side, the research is very clear, every brewer should be a LO2 brewer.

(M) Describe your general brewing process, including hot and cold side operations.

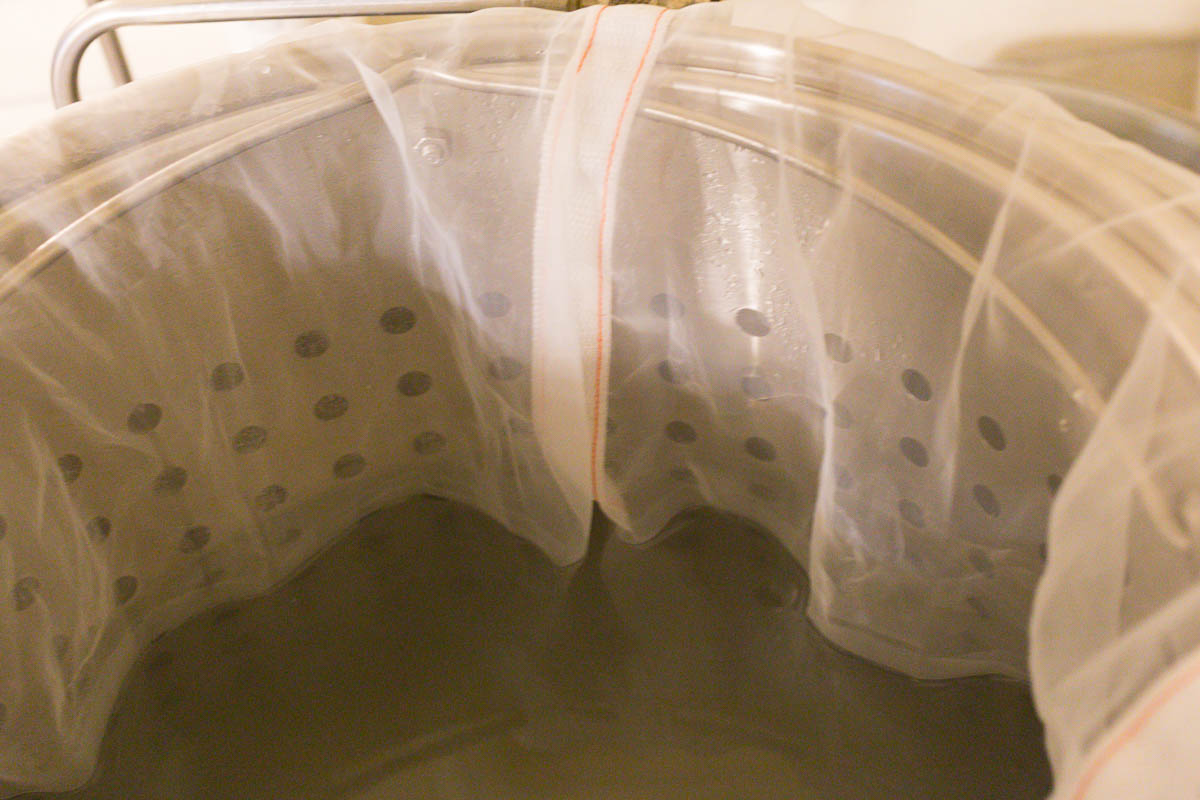

(Ric) I brew 5 gallon batches in a BIAB system with recirculation. I condition the malt before milling. I use RO water for light beers, and Austin water treated for chlorine/ chloramines. Most of my mashes are hochkurz (step mash), adding a protein rest for dark beers. I sparge for big beers but not for normal beers. I normally bitter via first wort hops, and boil 90 min for pils malt and 60 min for the rest of the beers.

I use an immersion-chiller, and transfer the beer to an auxiliary fermenter without much focus on the hot break. I chill this fermenter to almost freezing over 12-24 hours and then transfer to the primary. Whether starting from dry, liquid or slurry, my pitch is always active yeast.

All my beers are transferred to kegs for conditioning. I condition lagers via spunding valve. I let my ales finish fermentation and then I keg them with table sugar and gelatin. I bottle big beers without kegging them.

Conclusion

What may be lost in all of this is that Ric's system is designed with brilliant simplicity. A single vessel with an electric element, BIAB, circulation via short lines with a pump, eliminates the potentially unnecessary complexity of a RIMS or HERMS. Even if using a cooler or other mash tun configurations, simplicity works to your advantage. This should be very clear in contrast to my post about tightening up my Brew-Magic system. Simple techniques, such as a mash-tun cap and gentle transfers, as well as fewer possible points of failure, go a long way to managing oxygen uptake.

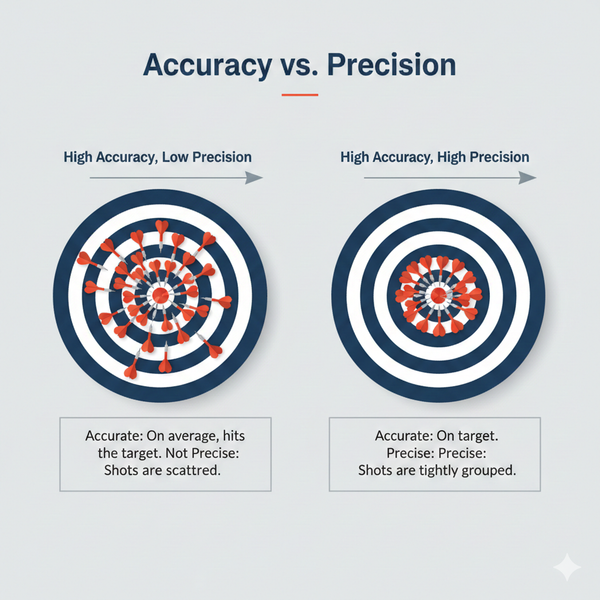

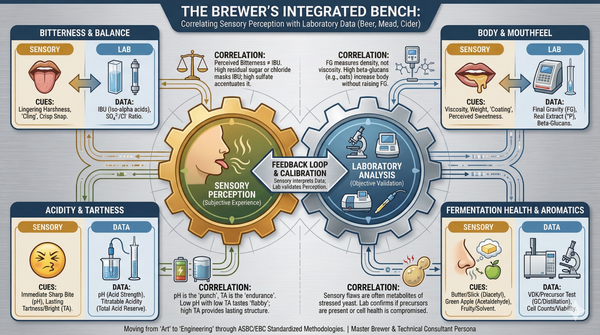

Something that Ric and I have discussed in detail is that nearly ALL of the scientific research on oxygen's role in brewing comes from commercial and academic research looking at mass manufacturing scales. The relevance to homebrewing, as he mentions, has not been proven, yet the principals remain. Science is science after all. So while I continue to explore in a more sloppy manner, Ric is systematically testing variables. Of course, neither of us have access to labs and equipment required to prove anything. That leaves, for now, subjective sensory evaluation.

Ricardo's process is not as tightly rigid as proposed by many of the LODO proponents, despite his hawkish attention to detail. His process is based on sound fundamentals; proper water chemistry, mash pH management, excellent yeast and fermentation hygiene. Perhaps more importantly, his procedures are consistent and predictable, which allows Ric to experiment by changing a single variable or troubleshoot a problem. I always learn something new brewing with people!

Ric's Go-To Helles Recipe

[beerxml recipe="https://storage.ghost.io/c/c2/87/c2876a49-5c65-4965-946c-679dac007e84/content/files/2025/11/go-to-helles-2017-2.xml" metric="true" mhop="true" download="true" style="true" mash="true" misc="true" actuals="true" fermentation="true" cache="1"/]