The Lab-First Paradigm: A Framework for Consistent Making

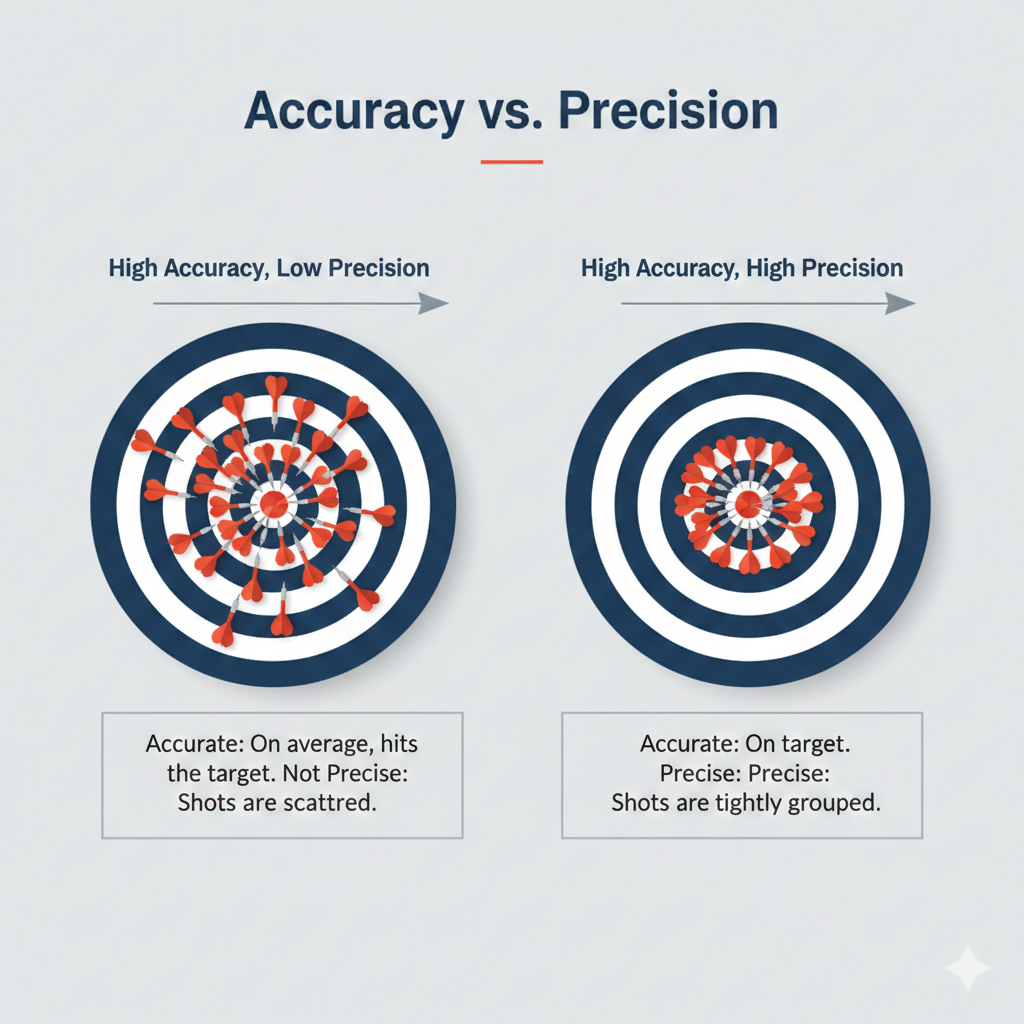

To bridge the gap between a lucky batch and a repeatable masterpiece, we must disentangle three terms that are often used interchangeably but represent distinct physical realities in the brewhouse: Accuracy, Precision, and Consistency.

In the commercial setting, "good" is the baseline, but consistent is the requirement to ensure customer acceptance and consistency batch to batch for house beers. To bridge the gap between a lucky batch and a repeatable masterpiece, we must disentangle three terms that are often used interchangeably but represent distinct physical realities in the brewhouse: Accuracy, Precision, and Consistency. Of course, you need to ask yourself if this matters to the way you brew. What matters most is that you enjoy making.

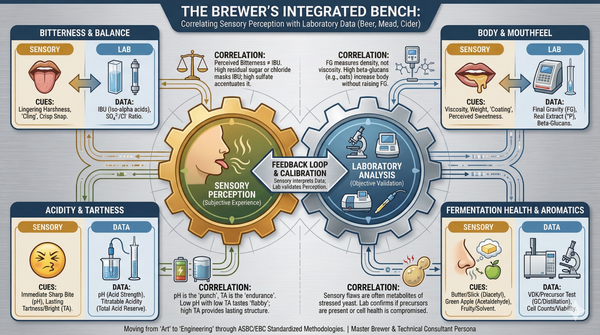

In a Lab-First framework, we don't just "measure" to fill out a notebook; we use high-fidelity data as a system of risk mitigation.

The Foundation: Accuracy vs. Precision

In professional brewing science, we do not simply record numbers; we verify them. To understand the data in our logs, we must distinguish between the Truth and the Grouping. We use the mechanics of a Lunar Lander to visualize this relationship:

- Accuracy (The Navigational Zero): Accuracy is your orientation. If your sensors tell you that you are 100km above the surface when you are actually at 90km, your "truth" is wrong. In the brewhouse, accuracy is Calibration. If your NIST-certified thermometer is off by 1°C, your enzymatic conversion and alpha-acid utilization are based on a lie.

- Precision (The Mechanical Constant): Precision is the repeatability of your thrusters. If you can fire an engine for exactly 3.00 seconds every time, you are precise. In brewing, this is Process Control. It is the "muscle memory" of the grind, the flow rate of the sparge, and the consistency of the boil-off.

Hardware & Readiness: The Integrity of the Sensor

A tool's "grade" is irrelevant if its state of readiness is compromised. A Lab-First brewer treats their sensors with the same reverent maintenance a Michelin-starred chef affords an expensive carbon steel blade.

The chef hones the edge before the first cut and wipes the blade after every cutting session, knowing the metal is reactive and prone to decay. Our sensors are no different—they are biological and chemical interfaces in a state of constant entropy. We must move past the idea that our tools are inert, indestructible objects like a chrome-plated wrench.

- pH (The Living Electrode): The glass bulb of a pH probe is a delicate, hydrated gel layer. If it dries, it dies. We dual-point calibrate ($4.01$ / $7.01$) before every "flight" and rinse with DI water immediately after every sample to prevent protein fouling.

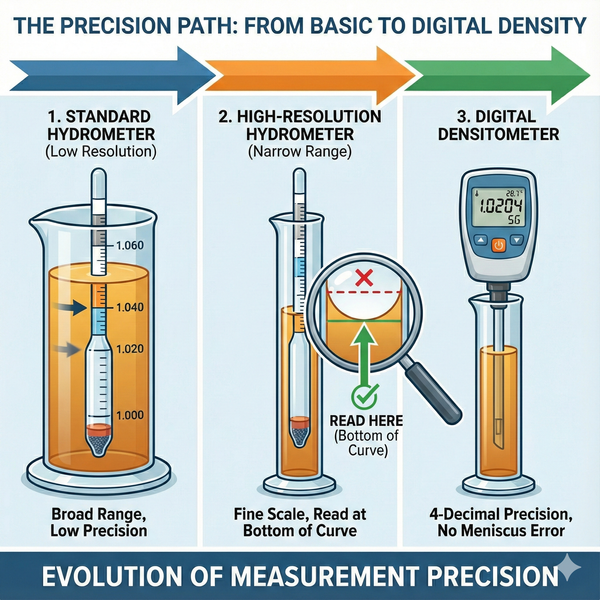

- Density (The Optical Interface): Whether using a fine-scale hydrometer ($0.0005$ SG resolution) or a digital density meter like an EasyDens ($0.0001$ SG precision), the surface must be pristine. Residual sugars create microscopic films that throw off refractive indices or U-tube oscillations.

- Power (The Electronic Constant): Low battery voltage leads to erratic sensor data. We replace batteries on a schedule, not upon failure, to ensure a stable reference voltage for the digital-to-analog converter.

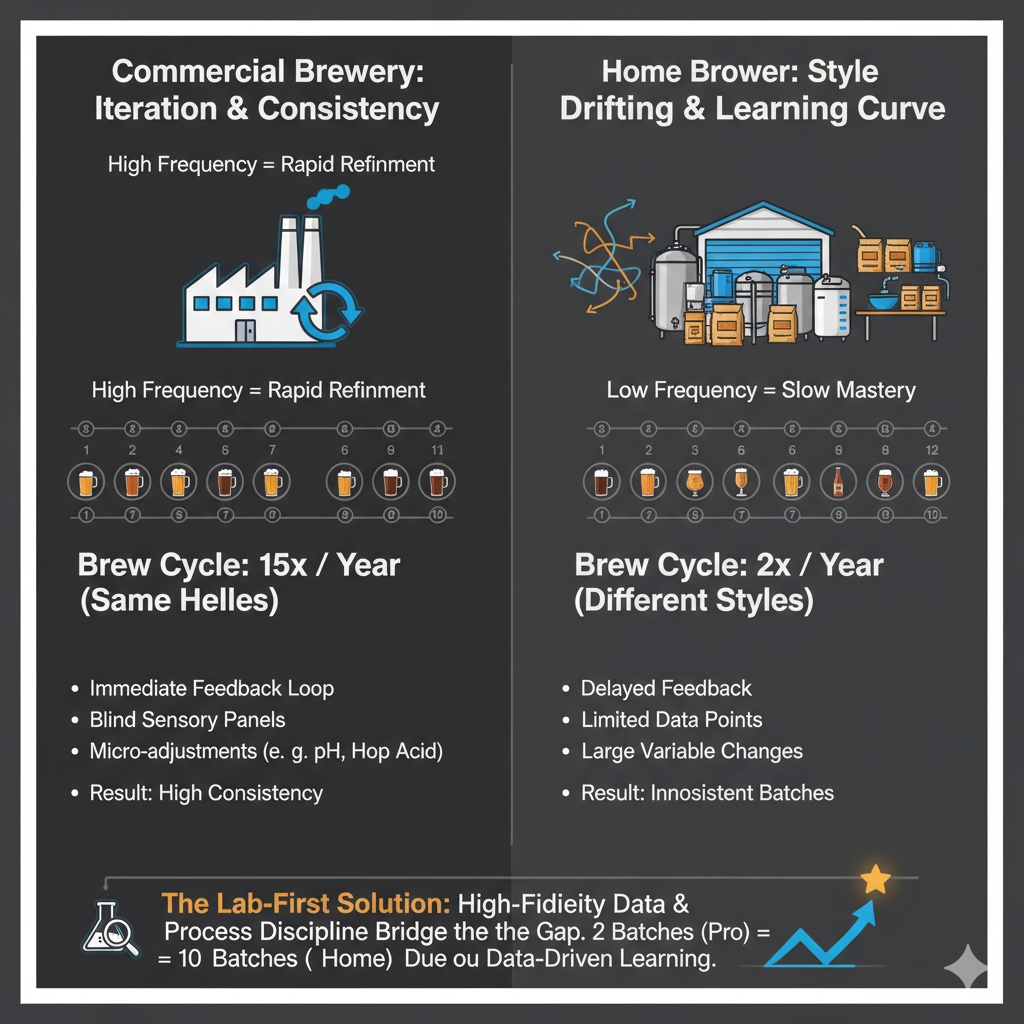

The Iteration Gap: Data as a Proxy for Frequency

A regional brewery achieves consistency through Frequency. They brew the same Helles 20 times a month, allowing them to "feel" when a process drifts through sheer repetition and blind sensory panels. They develop muscle memory and instinctively know when there is an issue, and how to save that batch.

As artisanal makers, we are often "Style Drifters." We might brew a specific recipe only twice a year. We lack the frequency to build "brewhouse intuition." Therefore, we must use High-Fidelity Data to bridge the gap. What a pro learns in two batches through repetition, a home-scale maker might take ten attempts to master—unless they use laboratory-grade precision to shorten that curve. High-resolution logging is our "spotter" in a low-frequency environment.

Targeting: The Mission Specification

None of this technical rigor matters if the mission lacks a defined destination. Every brew must be treated as a Technical Specification where we define our targets and our allowable Tolerances. We move away from vague calendar deadlines and focus on Critical Path Milestones.

| Metric | Target | Tolerance | Milestone / Trigger |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extract (OG) | 1.092 SG | ± 0.002 | Post-boil / Pre-knockout |

| Mash pH | 5.25 | ± 0.05 | 15 min into conversion |

| Attenuation | 85% | ± 2% | Stability over 72 hours |

| VDK (Diacetyl) | Negative | N/A | Forced Diacetyl Test pass |

The Feedback Loop: Remediation and Flagging

Excellence is achieved when your Actuals consistently fall within your Tolerances. However, the reality of the brewhouse occasionally requires "on-the-fly" corrections. This is where the integrity of your data is tested.

The Integrity of the Deviation

If you miss your pre-boil gravity and add DME to "fix" the OG, or if you over-dilute and have to boil longer, you must document these interventions with extreme care. While these actions may save the beverage, they move the batch off the "Clear Path" of your intended process.

- Document and Flag: Any mid-process correction should be explicitly flagged in your data as "Process Modified."

- The Forensic Value: A late addition of DME or an extended boil changes the Maillard profile, hop utilization, and mineral concentration. If you don't flag these deviations, you will lose the ability to troubleshoot why Batch #4 tastes different than Batch #3, despite both appearing to have the "same" final numbers.

The Rinse and Repeat of Mastery

- Define the Spec: Set targets and tolerances before heating strike water.

- Audit the Deviation: If you miss a tolerance, identify the root cause using calibrated tools.

- Refine the Plan: Adjust one variable at a time, rinse, and repeat.

Consistency is the statistical confidence that your next batch will land within your defined tolerances without the need for remediation. By treating your brew day as a flight plan with milestones—and a forensic record of deviations—you achieve a professional level of command over the craft.