Mead, Part 1: Mead Making Accelerated

I have this little problem with a mead obsession.

I find something, try it, and like it, then I am all in with a hyper-intense focus. The result is a lot of random hobbies that start to compete for my time, focus, and pocketbook. Mead is one of my major passions, but I approached it with a more ordered and specific plan than my long road in brewing.

If you don't know what mead is, stop reading this and find a local meadery or grab some on the internet (some suggestions are below). A great premium grocery with a diverse wine selection (always talk to the wine/beer manager) may carry mead (or "Honey Wine"). Then chill (48F-53F) and pour a glass. Smell, observe and taste. Then come back and read along. If you are near Austin - hit up my good friends and mentors at Meridian Hive Meadery!

A few highly regarded US Meaderies with Internet Sales (assuming they can ship to your state or country):

- Prairie Rose Meadery; I personally enjoy Star Anise and Blackberry.

- Moonlight Meadery; Kurt's Apple Pie and Utopian ($$$) are amazing.

- Melovino Meadery; Love me some Sweet Sorrow and Tempted to Touch.

- Superstition Meadery; Safeword and Aphrodisiac are wonderful.

- Rabbit's Foot Meadery; Odin is both delicate and complicated. Great traditional!

There are many more missing from the list, but interstate distribution is complicated and expensive. Any mead from the above makers will be awesome, I promise! If you are anywhere near Detroit, then hit Schramm's Mead. You will not be sorry. Regardless, you might be able to find some of these providers in a great wine or bottle shop.

Follow competitive events like The Mazer Cup or Mead Free or Die to discover the finest international commercial meads and home mead makers. Seek out your local mazers methiers and support them!

Mead is an ancient fermented beverage made from honey, water, the occasional spice or fruit, and yeast. Most know it as a Viking drink fueling berserker raids (but also spiritual and medicinal), or even found earlier archeological references from Africa (Tej continues to be made using a bitter herb) and Mesopotamia. While I love the mystique and nostalgia of so-called authentic beverages, this is the last you will hear about that in this article. Like beer, cider, and wine, today's meads are MODERN, sophisticated, and extremely diverse, and refined. The nostalgia and authenticity is largely a marketing message.

EDIT: I just learned that a mazer is simply the traditional wooden cup for drinking mead and not a mead maker. The actual terms should be mead makers or methiers.

As a home beer brewer, you may have most of the gear and basic knowledge to produce a very good mead. With the addition of great information on the internet, your shot at a great mead the first time out is greatly improved.

Planning for a Successful Mead:

My first mead attempt was a Joe's Ancient Orange mead (JOAM), and it took a long time to be drinkable. While very delicious, expect to wait at least a year or more before you have a fully integrated drink with the basic instructions. I nearly gave up on it. If you are impatient, as am I, then there are faster approaches to shorten time to a tasty finished product than just pitching and waiting.

I also found honey in bulk, 1 gallon (12 pounds) or 5 gallon (60 pounds) buckets. This can cut the price of your honey in half or more! Honey can be expensive as an ingredient. I would encourage you to start with a local raw wildflower honey (look in farmer's market and ask about bulk prices) and get to know the business owners. Most commercial branded honeys are highly filtered and processed, and with some of the import tricks being played with substandard, adulterated or contaminated honey. It is important to know your source. Supporting your local apiary also supports your local farmers as bees are critical to our crops and produce. Local wildflower honey will bring the character of the local nectar sources (terroir), dramatically affecting the key character of your mead - a truly local product. While specific honey varietals (Orange Blossom, Tupelo, Meadowfoam, etc.) display unique and wonderful honey character, the premium and shipping can dramatically increase your financial risk, in a batch. Brew a few batches of wildflower based meads until you are confident enough to risk the additional costs.

Finding experienced mead makers willing to mentor may help to address most of your process questions. If a local home brew club doesn't have great mead makers, look to online communities. Participating in brewing competitions (even judging) will often reveal the great regional mazers and provide some leads. Beware; you maybe confronting "old school" versus modern mead making techniques and attitudes. Either way - there is a lot of knowledge to adsorb. Always approach with respect.

I did a mead swap with an internet friend who makes 100+ gallons of mead a year, and bulk ages the "old school" way - and they were each wonderful, flavorful, and incredibly complex (thank you Pete!). Well crafted and aged - and sometimes boozy meads - can create intensely beautiful and sophisticated flavors. He uses no chemistry to stabilize; just lots of time, gentle racking technique and a lot of experience with cider, wine, beer, and mead making. Pete allows his mead or wine to become what it wants to be, with little interference. He is also a very patient person; I am not.

On the flip side, modern mead makers manipulate process, technique, and applied chemistry to control fermentation (speed, intensity, and phenol/ester profiles), clarification, and stabilization, shortening time to maturity and of an equal quality. While you maybe concerned about adding "chemicals" to your product, none of the proposed additions are dangerous and are commonly used in the finest wines. Mastering these (old and new) techniques allow you to focus on recipe creation - building unique flavors that compliment your honey and yeast choices. I also fall into the no-boil camp, even with raw honey. To be clear, we are looking to shorten the time to a finished product to 2-3 months (or even faster) from a more traditional 6-12 months, without compromising quality. Think of it like brewing a strong Christmas beer.

I also read voraciously. There are more than a few mead focused books, but Ken Schramm's, "The Compleat Meadmaker", is likely the most respected and well written book for the home and commercial brewer. The book is slightly dated, but the recipes and processes are bulletproof. Schramm's approach is both scientific, romantic, and culinary - and if you EVER get a chance to have a bottle of Ken's "Black Agnes" - do it. A more modern and science-based approach, but perhaps a bit more sterile read, is Steve Piatz's book, "The Complete Guide to Making Mead." These two books are the basis for modern mead making, focusing on yeast rehydration, yeast nutrient strategies, and importantly, recipe development. Both authors are friendly and personable, and active at conferences like HomebrewCon. Other great resources, referenced in this series, are: the Gotmead Forum, Meadmaderight.com, the Mead Reddit, and Meadmakr.com. A little Google-fu will bring a lot more information, but these are my trusted go-to-resources.

I would be amiss not to mention the American Mead Makers Association, which is dedicated to growing the craft mead industry. I have an individual membership - and I encourage you to join!

To review:

- Educate yourself on mead and explore various approaches and philosophies and styles, and choose a path that most resonates with your sensibility and confidence.

- Find a mentor. Most home mead makers are very generous and open books. Be respectful, listen, and ask critical questions.

- Drink good mead, both commercial and home brewed. Figure out what you like and do not like. Not all meads are refined and delicate, and not all meads are mouthfuls of juicy fruits or spices. There is a broad and diverse range of flavors, mouthfeel, and experiences. Take good notes with a wide open mind!

- Doing this before making your first mead will give you some perspective and a variety of opinions on how you wish to approach your goals. There is no single path here, but we can avoid pitfalls and increase our odds of success.

- BONUS: Become a BJPC Mead Judge. Technically, a Mead Judge is an endorsement and not a Certification. There are so few mead judges that I nearly always get a place for mead flights in comps, but remember you cannot judge a category you have entered. You might find yourself with an avocado, cilantro and jalapeño monstrosity in the glass in front of you! Dive in - you might be surprised! I won several awards before becoming endorsed, but the class made me a much better methier!

Preparing for your first mead:

Enough of the rambling; the next article will outline an introductory mead recipe and strategies to ensure an ordered and healthy fermentation, as well general recipe ideas to twist up the mead to something to your personal preferences. In the meantime, you may need a special trip to your LHBS to grab a few things. The recipes will focus on a 5 gallon batch of mead, but can be scaled linearly (with a few exceptions) up or down. We will assume you have fermentation buckets, carboys, and a hydrometer. You may wish to dedicate racking equipment, so a set of canes and hoses maybe in order.

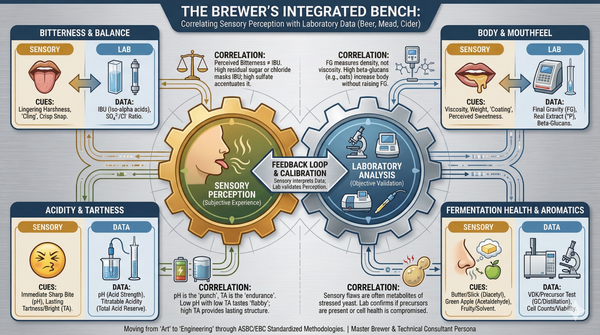

Attention to detail, lots of creativity, and a little OCD fit the modern mazer approach. We are going to explore what seems complicated at first, but is much simpler than advanced all-grain brewing. Bringing in some of your tools, such as a pH meter, water chemistry knowledge, and detailed note taking, will give you a solid leg up in making a great mead.

A mead prep checklist, getting prepared.

Links are provided for reference, with no affiliation:

- A wine yeast of your choice. I suggest Lalvin 71b-1122. One packet is adequate for a standard 5 gallon sweet mead. Ale yeasts can be used, but I find wine yeasts more predictable and better documented for mead. For AHA members - Fermenting Mead with Ale Yeast NHC preso and the May/June 2016, Zymurgy for an article comparing ale yeasts in mead by Billy Beltz.

- Go-Ferm Protect. This product prepares the yeast during hydration for the lag period after pitching.

- Either pick up both Fermaid K + DAP (diammonium phosphate) or just a package of Fermaid O. The previous are used together as Staggered Nutrient Additions (SNA), and slightly cheaper. Fermaid O is used in Tailored Organic Staggered Nutrient Additions (TOSNA) but may require a special order from your local shop.

- 2-4 pounds per gallon (of your batch) of wildflower honey scaled to your batch size. 2 pounds honey per gallon (hon/gal) produces a dry mead, where 4+ pounds hon/gal creates a sweet mead. Look for local wildflower honey (raw) that you really like. Taste the honey and note its flavors. Make a small tea, dissolving a few teaspoons in 2 ounces of hot water and note those flavors. Keep this information handy - fermented honey tastes different, but carries over some of the aromatic and flavor notes.

- Potassium Carbonate or Potassium Bi-Carbonate to help buffer acidity during fermentation to prevent yeast stalling out. A pH meter or quality pH strips are also useful as a diagnostic tool.

- 1 to 4 gallons of grocery "Spring Water" for a 1 or 5 gallon batch. If you have moderately hard tap water that tastes good, you can use this, but you will need to treat for chloramine or chlorine using Camden tablets or potassium metabisulfite. If tap water is used, then use 1/4 of a crushed Camden tablet or equivalent in 5 gallons of tap water. Mix this well to dissolve and let stand for about 5 minutes before use. Avoid pure reverse osmosis or distilled water until you are prepared to build water with mineral salts.

- A fermentation vessel (bucket, carboy, or conical) that allows at least 1-2 gallons of head space.

- A device to degas the must. Winemakers often use a whip that attaches to a drill to facilitate this. A large hand whisk works well in buckets. Both need to be thoroughly cleaned and sanitary.

- Secondary carboy (PET or glass), sized to your batch to minimize headspace, and air locks for aging. Always immaculately clean and sanitized. I prefer glass for this step to slow oxygen uptake, but handling must be treated delicately. Glass is slippery and can break causing serious injury. I like to put my glass carboys into a crate for easier handling.

- K-Meta and Sorbate. K-Meta (potassium metabisulfite) is used to scavenge oxygen during racking. The combination helps to stabilize the final product and prevent further fermentation after racking. NOTE: if you are sensitive to sulfites, then avoid this. There are other strategies to stabilize that require racking and filtering, but may take much longer. Your mead will take much time to stabilize without these additions or procedures. It is a personal decision.

- Super-Kleer Finings. This two stage addition to the finish product will produce a high clarity in a short period of time. If you are vegan or allergic to shell fish, then avoid this product. Other finings may be preferable. Combined with an absolute filter step (about 0.45u) you can stabilize a mead and ensure a very bright and high clarity of commercial quality.

- Finally, Tartaric Acid (as a mead judge, please avoid acid blends) and wine tannin (I prefer Tannin FT Blanc) for finishing and adjusting the final acid:tannin balance. Other acids (malic, ascorbic, and citric) can compliment specific styles, but are outside the scope of this series.

- Bottles or kegs, depending on how you plan to serve. You won't need this for a few months. If you want sparkling carbonation, then use champagne or belgian bottles that will contain the pressures required. These will need cork and cage. Kegs are convenient to force carbonate to petillent (low carbonation) or sparkling (champagne-like carbonation) without dealing with bottle conditioning, and perfect O2 free environments for long term aging.

- Tip: Use a garbage bag with a bucket or milk crate to contain the fermenter and catch spills. Degassing and sampling can be messy if not done carefully.

We need to ferment with temperature controls, at the least at an atmospheric temperature under 72F. The lower the temperature, the lower the initial ferment intensity, reducing the development of fusel alcohols, phenols and esters, and potential off flavors, while accelerating finished maturation. Lalvin 71B-1122 is a great yeast that can ferment into warmer temperatures with restrained off-flavors, but there are many great choices. If you can ferment in the mid-60F range, then off flavors will be minimized. That said, ambient fermentation at 70F with Lalvin 71B-1122 yeast (fermentation creates heat and the batch will be above ambient by 3-4 degrees) can create a great mead with a medium-low fusel profile and medium yeast ester profiles (which can be nice). Identify a large enough dark space as cool as possible to ferment, large enough to deal with your batch size. The goal is from must creation to clear and finished product in less than 4 months!

Join us for the next post: Mead, Part 2: Must Make Mead! - covering the must making process, a first recipe, discussions about yeast hydration, degassing, and nutrient strategies.