Improving your BJCP Tasting Exam Scores

Suggestions for improving your BJCP Tasting Exam scores.

This is a followup to my article: Judging and the Anatomy of a Scoresheet. I have started grading BJCP tasting exams (working toward Master) and have noticed a few common issues that are easily addressed and should ensure a fairly easy shot at an 80 score. What follows is pretty straightforward advice that applies to the BJCP Beer/Cider/Mead Tasting exams.

Another disclaimer. I am not representing the BJCP in any way. I am fortunate to be BJCP National ranked, with a Mead Endorsement. What I write here is my opinion, nothing more.

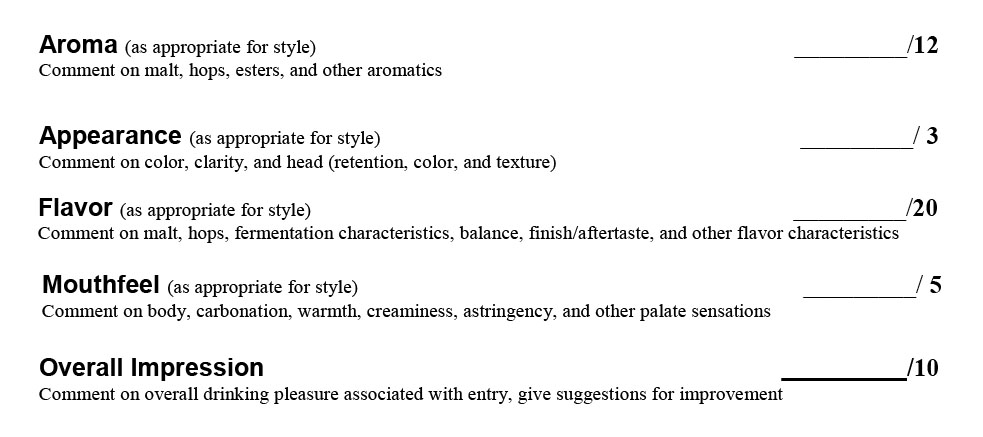

My strategy requires just a little bit of analysis of the 2018 BJCP Grader's Guide. The exam requires the analysis and writing of scoresheets for 6 beers, meads or ciders, in a 90-minute limited timeframe. If we carefully look at the scoring mechanics per sheet, we see that 100 points are granted per sheet and broken out into Scoring Accuracy (20) and Sheet Content (80). Each sheet is considered individually, and the overall assessment is an average of the 6 sheets.

Remember that this advice is for test-taking, and not necessarily for normal judging procedures. That said, as someone that still enters competitions regularly, applying most of these tips will dramatically increase the perceived value and credibility of your scoresheet.

Scoring Accuracy (20) compares your score against the proctors' consensus score for that beer/mead/cider. If you are within 9 points of variance, you will still get 50% or 10 points. The remaining 80 points fall into Scoresheet Content competencies as described below.

Perception (20): Each scoresheet is judged against a rubric created from the proctor scoresheets and points are deducted for missed flaws, errors in aroma, appearance, flavor and mouthfeel perception. However, if the participants' consensus finds something that the proctors missed, then no penalty should be given.

Descriptive Ability (20): You must describe both the intensity and character of aroma, appearance, flavor, and mouthfeel of your experience.

Feedback (20): Provide constructive and useful feedback on how to adjust recipe or brewing procedure to produce a beer/mead/cider more accurately to style. Feedback should also address solutions to flaws and areas where you deducted points.

Completeness/Communication (20): All written information should be well-organized, utilize all available space, and fully describe the judging experience. All fields should be filled out and utilization of appropriate checkbox descriptors and the Stylistic Accuracy, Technical Merit, and Intangibles box filled.

Corresponding scores per sheet are then correlated to expectations of experienced judging levels:

- 12-13+ = Recognized

- 14-15+ =Certified

- 16-17+ = National

- 18-20 = Master

Graders then enter their scoring data into a spreadsheet, consult with each other for consensus and feedback and present the spreadsheet to the AD, who audits scores and may override if there are large deltas or lack of consensus between graders. The grading process is long and subjective but no more so than judging a beer. Each score sheet takes me about 20-30 minutes after I have gone through and created the rubrics, assuming the sheet is legible.

The Strategy

Maximize those things that YOU control as an examinee.

It's really that simple. Let's roll through the 5 areas, and I'll make specific recommendations.

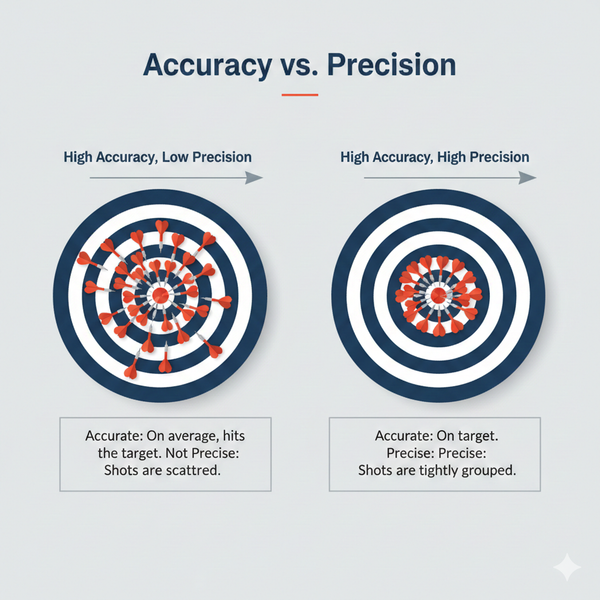

Scoring Accuracy (HARD): Nothing replaces experience in judging. Judge at every possible opportunity and sit with challenging flights and excellent judges. Come in to learn and ask questions. Learn to be quiet and efficient in how you approach each entry, and mostly, be honest. Don't fill up a sheet with stuff you imagine - just what you experience. Judge what is in the cup in your hand. Don't allow another judge to run over you or influence your perceptions. Go back and read Judging and The Anatomy of a Scoresheet.

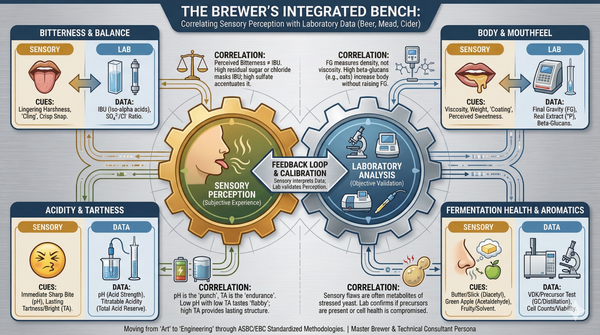

Perception (HARD): This takes training and a lot of practice. Learn to identify common off-flavors but also develop a lexicon of aromas and flavors that you can draw upon to describe something. Beer, mead, and cider, all present with different general characteristics and require specific study. Many clubs or BJCP groups offer off-flavor and aroma classes, and this is a good place to start. If you are in a situation where you can access actual off-flavors (say someone points out a butter bomb in a competition), see if the comp coordinator will let you taste that beer. Take mental notes of that association of senses and calibrate your senses to those of qualified judges.

Two things that are commonly missed are off flavors/aromas and things that are missing or misalign a beer to style. For example, a little diacetyl is ok for some British ales, but it needs to be integrated into the flavor and not off-putting. Or perhaps a big Russian Imperial Stout is missing a warming effect from the alcohol or has a strong vegetal character from roast malt. You need to ability to suss out these things and assign them as in/out of character for a given style.

Not everyone can sense DMS, Diacetyl, Acetalaldehyde and many other faults. There are Masters that are blind to many of these faults. Graders take this into account (or should). Know your limits, and always judge what is in the cup in front of you!

Descriptive Ability (EASY): When I took my last tasting examination I wrote IQ next to each area. IQ stands for Intensity and Quality and is a reminder for me to address each of the subareas under aroma, appearance, flavor, and mouthfeel with specifics.

Develop a personal canon for intensity and do not use ranges; medium-high, not medium to high. Use your intensity descriptions consistently and avoid using fluffy words, especially good or awesome.

Develop a vocabulary for malt, ester, phenol, and hop characteristics.

For example, the aroma of an IPA:

"Hop aroma is very high and pungent, with medium-high tropical fruit aromas, mango, low dank note. Malt intensity is low, with low levels of cracker and bread crust and a low note of caramel. Esters are very low, buried under the tropical hops, but suggest a clean fermentation profile."

Compare that to this:

"Lots of hops. Fruit salad aroma. Good malt. No esters."

This last description provides no levels of intensity and the lightest sense of character. Words like "Lots" and "Good" are not measurable. Use the categories "comment on" list and check off the list as you go. Even if you are not accurate, at least you get more credit during grading.

Develop a descriptive template that eliminates the writer's block I see so often with new judges. Utilize the "Comment on" list and plow through.

Feedback (EASY-ISH): My strategy is to develop pat "answers" to most of the off-flavor/aroma issues that may arise, as well as recipe recommendations to increase alignment with style guidelines. This way I can provide SPECIFIC and ACTIONABLE advice, without making assumptions.

I am going to jump onto a soapbox here and say, don't fill this section for the TEST with fluff comments like "I'd finish a glass of this." Save that for competition judging. That is empty filler and bad when that space should be used to provide that specific and actionable feedback on off-flavors, balance issues, and style problems. Be thoughtful and relevant and don't just parrot bad advice. #endrant

Here are a few examples, specific to mead:

"To avoid fusel alcohols in this mead, study up on SNA or TOSNA nutrient addition schedules and adopt them. Rehydrate your yeast in 1.25x by weight in GoFerm, and use pitching rates of 1-2 grams yeast per gallon for under 1.090 gravity, 2-3 grams per gallon if over 1.090. Temper the yeast slurry to pitching temperature, and ferment at the lower temperature range recommended by the manufacturer. Avoid stressing the yeast."

"The harsh woody astringency causes a balance issue. Consider blending with a softer mead and/or sweetening with honey to reduce tannin levels. If using oak in secondary, taste throughout secondary aging until the level is just right and remove the oak. You may also wish to consider using a different level of char or varietal to better match the honey character. Adjust acidity and sweetness after oak-ing to taste."

"The high alcohol level, combined with the very dry finish, is unpleasant. Consider using less honey to reduce alcohol levels, and a light touch of sweetening with raw honey to reduce harshness. After back-sweetening, let rest for a few days to integrate and then adjust acidity and tannin levels to taste. Or blend this with a sweet version of traditional to taste."

Or, "The tart-n-tiny finish is distracting from a really excellent expression of honey character. Explore other acid additions. Consider bench trials of your traditional using different acids (citric, malic, tartaric, ascorbic, phosphoric) to see which provides the best experience and a pleasant lingering aftertaste."

Always think, SPECIFIC and ACTIONABLE feedback. Remember that the proctors are not providing this kind of feedback, rather their overall impression of the beer/mead/cider, so it is important that you address either the key off-flavors/aromas and any tweaks necessary to bring the sample more in line with the style or improve the experience.

It is OK to give your opinion, such as, "I would like…" but only after you have addressed the important and salient issues that you detected.

Completeness (EASY): Fill out every relevant line, check every relevant box, and do not leave any white space around the aroma, appearance, flavor and mouthfeel areas. Please expand in to the extra white space to the left (in an orderly manner).

Make sure to align your scores with the box at the bottom, and tick the sliders that represent stylistic accuracy, technical merit, and intangibles.

Make sure to check off the Descriptor Definitions and as a bonus, write something next to clarify, such as high, low, or to style.

Completeness also means writing legibly with orderly sentences and paragraphs. Sentences make sense when proper grammar and syntax are used. So many people have horrible handwriting, but please make an effort. Block lettering is appreciated.

Finally, write with confidence. As mentioned, ranges are not appropriate and give a sense that you are just not sure. Same with using words like "maybe" or "perhaps" in providing feedback, unless you are giving options. Those are not SPECIFIC words. Be firm in what you are expressing, without being arrogant. Take the time to fully figure out what is in that cup, and come back to it if you feel rushed.

TL/DR

- Do the work and learn both the styles and how off-flavors/aromas present to you personally.

- Use the indicators under each category to specifically address each issue and check them off.

- Always use an INTENSITY statement for each issue and describe it's QUALITY. Write IQ by each area if needed as a reminder.

- Use all of the available space needed to get your points across. Feel free to meander into the white space near the descriptors.

- Provide both SPECIFIC and ACTIONABLE feedback that addresses identified flaws or that will make the recipe better fit the entry category.

- Be confident. Judging is about YOUR opinion and not someone else's. Judge what is in front of you and don't allow yourself to be influenced or biased. That said, know your limitations.