Damn the Torpedo... or Hopback, Part 1

It was absolutely frigid. Frightfully cold, and I say this with the slightest nod to friends and family that are north and north east getting pounded with snow, sleet and ice and truly freezing again. After 20 years here in Texas, I have lost my tolerance for the cold. My buddy Neil from Scottish Brewing and I got our heads together to collaborate on a Hopback-based IPA - something to really push the limits of the 1.5 gallon Hopback I got from the folks over at Stout Tanks. Our discussion rolled through a couple of IPA ideas - Neil is a huge fan of NZ hops, and I am more of an APA kind of person. We discovered that we both adore Bell's Two Hearted that features such incredible flavor and aroma from just Centennial hops. So we knocked around a few ideas:

- Pale, with just shades of orange and gold, polished bright, star bright

- Dry, featuring high levels of sulfate and good attenuation

- IPA strength, so shooting around 70 gravity points and around 60 IBUs using whirlpool calculations in BeerSmith

- All late hops - no hops in the boil. Stuff the hopback and recirculate through the kettle

- Centennial and Cascades, classic and bulletproof pairing of American Centric hops

Clearly this is not in our wheelhouse, but not that difficult to imagine. I am calling it Cascadentennial IPA. Might just not be an IPA... will see.

The recipe is here (Thanks Derek Springer for the BeerXML plugin!):

[beerxml recipe=https://storage.ghost.io/c/c2/87/c2876a49-5c65-4965-946c-679dac007e84/content/files/2025/11/hopbackale1-2.xml metric=false cache=-1]

The recipe above doesn't pickup the fact that the hops are calculated for a 45 minute hopstand... I assure you that the BeerSmith file is set correctly.

Martin Brungard pointed me to the seminar at NHC 2014 last year by Matthew Brown, called No Boil Hop Beer. If you are an AHA member, you can find the presentation at the AHA front page under seminars. The gist is that through experimentation, Mr. Brown built a small hopback and used it to create a series of beers that had no hops at all in the boil. He lautered through the full hopback and then a short whirlpool/circulation through the hopback at flame out (10 minutes). In this way - he split batch and measured the beer with only the lauter hops and the beer with the lauter and knockout hops. It was a fascinating concept.

The Brewday

As mentioned, the day was very chilly - and fought my system coming up to temperature. I heat my strike and sparge water separately, ensuring that the heat exchanger and accompanying plumbing is warm enough to help regulate the RIMS circulation when I grain in. A mistake led me to leave out a gallon of strike water, which was fortunate. When I looked at the 10 gallons in the tun, I was pretty sure that 28.5 lbs of grain would nearly max out the tun. So I moved the extra gallon to the sparge and re-figured my mineral additions (Pale Ale Profile, BWS).

I weighted out my base malts (twice lucky) and used the very last ounce of my 2-Row. The rest of the grist, Marris Otter, some Crystal 45L and Torrified Wheat were added and prepared to mill. The mill ate through the malt easily, but I managed to spill a little bit. The torrified wheat was incredibly fat - I believe from Fawcett. This got mashed-in whisking vigorously to ensure no dough balls formed. I decided to add in a few handfulls of rice hulls as insurance. The mash went essentially without a problem at 152° F for 60 minutes. We had to cycle the gas a couple of times as the temperature fluctuated more than normal. I confirmed a 5.42 mash pH at around 45 minutes, just a few hundredths high of my estimate of 5.39 using BWS.

We did not lauter through the hops (as in the NHC presentation) and decided to rely on the hot wort at flameout to create the required bitterness, aroma and flavor.

There was a small hiccup during lautering. I fly sparge, and the pump was pulling liquor from the HLT and somehow airlocked. Not a big thing, but I need to look for a possible leaky connection or bad gasket. We got it working again and finished the run off. The wort struggled to achieve a rolling boil, but finally made it. I used a touch of FermCap-S to ensure the very full kettle wouldn't foam over.

Remember - we are boiling without any hops. The hot break material formed nearly instantly, indicating that the pH had dropped to around 5.1 right away. As the boil progressed toward the Whirlfloc and Nutrient addition, I noticed that the break had formed a skinned cap on the top of the boil. It looked and behaved a bit like the skin that can form on a milk based soup. I pushed it and it folded up and was easily removed.

As we neared the flame out period, I got the hopback into position, and as luck would have it - the gas ran out. From a sensory perspective, all we smelled was malt during the boil - which was expected. But it was a strange sensation not having what would have been that intense hop aroma you would expect from 12 ounces of hops.

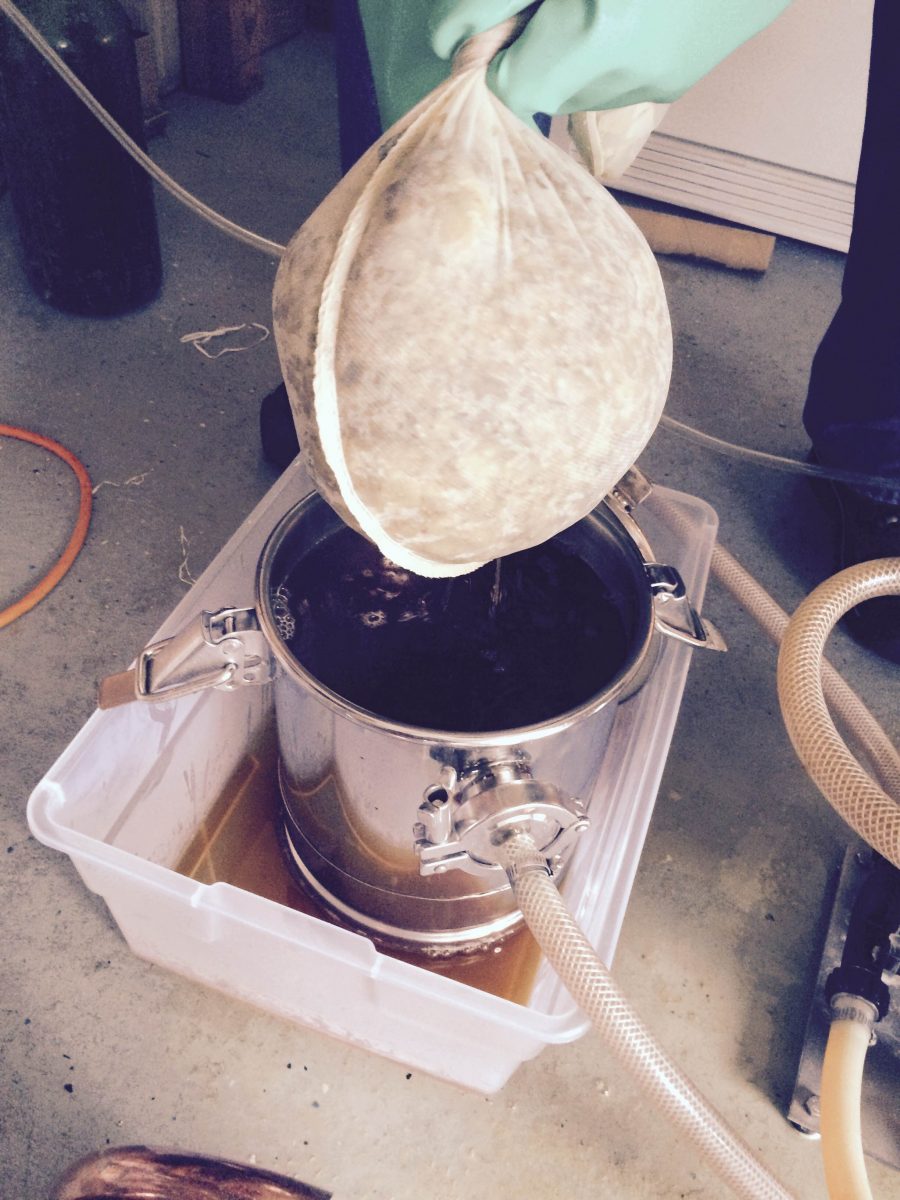

It had already been filled to the brim with 6 ounces of Cascades and 6 ounces of Centennials, tied loosely into a bag. We left the top open while the hot wort flowed into the vessel. As the hop bag started to float out, we secured the lid. Somehow, a portion of the bag caught under the silicon seal. This allowed the building pressure to cause wort to spray and then leak during the circulation period. There wasn't much we could do, and we decided to proceed with the circulation for a total of 25 minutes. Essentially using it a bit like a hop tornado vessel.

[embed]https://vimeo.com/120859312[/embed]

The circulation speed was tremendously slow, as you can see by the video. Usually the stream is quite strong, so those hops were tightly packed, which might have hurt extraction. Then rested for about 15 minutes while I connected to the fermenter and relieved the pressure in the hopback to install the fresh hop charge - another 3-4 ounces of cascades. This last charge still got very hot wort, and hopefully the oils were transferred directly to the fermenter without any chance of evaporation.

As I removed the massively swollen spent hop charge (the 12 ounces) I decided to squeeze the bag to recover as much of the wort as possible since we were losing so much to the leakage and adsorption. This was really the first time we noticed any traditional hop aromas you would find with a normal boil schedule. I squeezed about a quart and a half back into the kettle and a huge slick of oil formed on the wort. We added the finish hops and turned on the cold ground table water to my new convoluted counterflow chiller and was able to knock out and chill to about 66° F in just about 5 minutes. But it was clear that from a 14.3 gallon pre-boil volume, down to massive losses with the hops and leaking, we only had about 9.5 gallons in the fermenter. To hell with brew house efficiency...

At this point, we decided to carefully disconnect the hopback and dump the residual gallon or so of wort into the fermenter. I wish I had remembered to sanitize the exterior of the vessel, but I didn't. I hope that excess heat of the wort rolling through the hopback killed anything too bad. We were able to pitch at temp (64° F) shortly after.

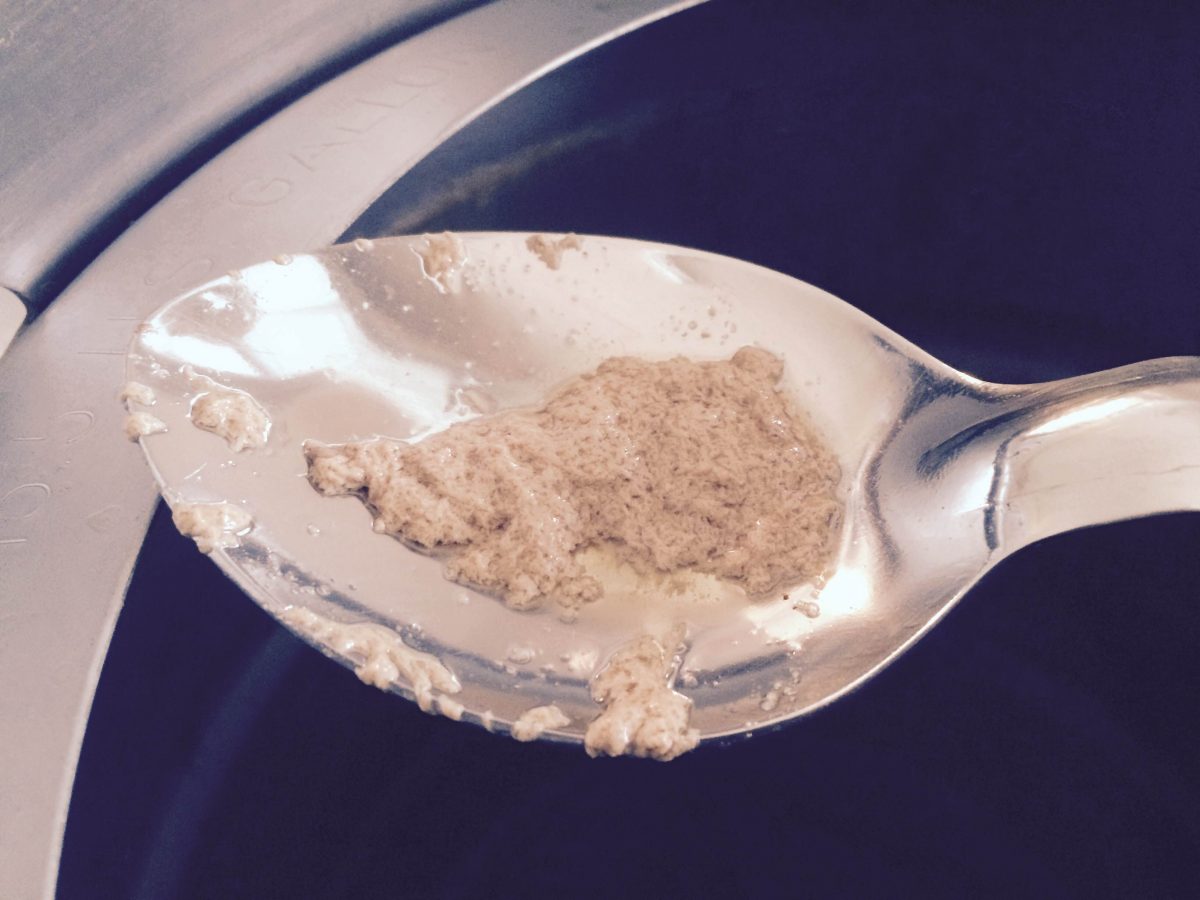

Remember that weird and crazy break material? Clean up was strange. The false bottom of the boil kettle caught and filtered a good deal of the hot break. The texture was a lot like soft tofu, held together in a gelatin-like manner, but cleaned up easily. The amount of break material wasn't excessive, but I am interested in pulling trub in a day or two to see what falls out as cold break. Even the leaking pools of wort on the garage floor had break material form as it cooled - very odd.

I still have a lot of floor scrubbing to do out in the garage. But it smells really great out there!

The beer is now fermenting at 64° F on a slightly oversized batch of rehydrated US-05. The gravity also came in a few points low at 1.065 rather than 1.070. Not sure where that went - but have seen this problem a few times when I use wheat. This is going to go for a few weeks as I don't have any room in my backed up beer pipeline, but we are already considering the possibility of shipping this keg out to NHC for club night. At the least, it maybe a nice and hoppy APA, but hopefully a solid IPA with immense hop flavor and aromas.

So to summarize, we did not lauter through the hops. We are counting on the BeerSmith calculation for a 45 minute steep/whirlpool stand of 12 ounces of hops. The finishing hops are calculated for 15 minutes. In actuality, we probably achieve the 45 minute stand, but the temperature of the kettle quickly fell to around 160° F and stabilized. This is below isomerization temperatures - so we really do not have an idea how this will settle out.