Calibration Series: Your Senses

Did you see that one coming? I am trying to put these in some order of importance, and while most times you would think about calibrating equipment, some of the most important equipment you already have. Our senses are incredibly sensitive tools if used properly, and particularly so when trained properly.

When it comes to beer, I have my favorite styles, and probably do not meander enough through the aisles of eccentric beers, but I do make an effort. When I am branching into a new beer recipe, I make a point of buying 4-6 commercial versions of that style. This allows me to assess the typical characteristics of that style, and understand if there are certain boundaries that are important. I then read recipes - hopefully from the vendor, if possible, and try to pick out those specific featured ingredients. I have to admit the malt forward German lagers make this very difficult for me, especially with hops (so I stick with traditional hops here).

You must be in good health, no sniffles, congestion, allergies, and away from any medicines or perfumes that will influence your perception. This is very important - a cold or sinus issues affect BOTH taste and smell, potentially hearing and eyesight if severe. Perfumes, lotions, even laundry scents can mask or be mistaken for specific aromas or change the taste and balance of something delicate.

Second, avoid strongly flavored foods or drinks for a few hours before a sensory session. Smoking, dipping or chewing gum - can dull or influence flavors and aromas (seems obvious, and some people can overcome this).

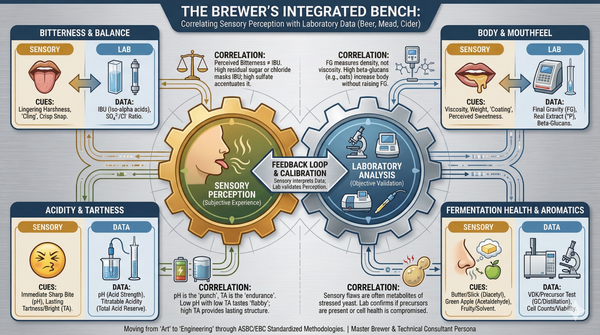

Sensory Evaluation: I am not going to get completely into this, other than to say, do not be intimidated. Yes there are related formal training programs, such as BJCP Certification for Judging or Cicerone, but you should be able to distinctly describe what you see, smell and taste when calibrating to a specific beer. A commercial calibration beer is often used in competitions, and is also useful to compare and contrast. Read other critiques (RateBeer, etc.) of a commercial beer, and see if you can identify the same flavors or characteristics. Use your own language and vocabulary - not everyone knows what lychee or gooseberry tastes like!

Using All of Your Senses on Brewday

Sight: Extremely important in the brew day. Visual evaluation of the equipment, hoses, ingredients ensures a smooth process, and hopefully fresh ingredients. Water should be clear, not turbid. Each grain has a distinct color, but should never have mold or fungus growing. Your equipment should be at least visibly clean, and all connections secure, valves closed (or open), the flame a bright blue with little yellow or soot. Humans still retain a sensitivity to movement, and use that to ensure no little ones (human or pet) is harmed in making your beer.

Sound: Also important, but perhaps more from an evaluative and comfort sense than anything else. Brewing to music (necessary for most brewers) is great, but should not drown out critical sounds: propane burners, pumps (cavitation or weird vibrations), bubbling of a boil, splashing of wort (perhaps dripping from a bad connection or leaks). Kids or dogs moving near 15 gallons of hot liquor. These are all elements of situational awareness that can keep your brew day safer.

For example: Since my system recirculates during the mash, I can hear when I am getting close to a stuck mash. The pump cycle seems to slow and the pitch deepen. There is also a distinct sound when the pump cavitates.

Touch: Not much to say about this, but learning to approach hot kettles and hot hoses properly is important. Use the radiation heat as an indication of when and how to pick up something. If it is too hot - handle carefully with proper gloves. Always treat chemicals as dangerous - use gloves. Note: the back of your hand can be more sensitive to heat than your padded palm and fingers - feel for heat there first, then determine if it is safe.

Smell: I should have kept this to the last, as it is my favorite. I love the smells of brewing. You should smell everything, including the water, malt, spices and hops. It should all smell fresh, no odors. Do be careful as breathing/smelling some of the brewery chemicals, or the powder from crushing malts can be hazardous and have long term effects.

For example, I accidentally left some old rinse water standing in my system's plumbing after I had prepped all of my liquor. Fortunately, I typically open the bottom drain valve to prime my pump and this pungent sulfur aroma hit me in the face as it splashed into the bucket. So while the strike water was heating in the MLT, I ran sanitizer from my HLT through the system. When I was done - no odor remained. Didn't want any of that nastiness in my beer!

Brewing is a feast of smells, I love the smell of doughy bread during mash-in, or the cleaner sweet malty smell of wort towards the end of the mash. The occasional smell of burning sugar caramel when wort drips onto a hot burner, and of course, the smells of hops hitting boiling wort! These should be in contrast to dangerous smells like propane gas (something is leaking!) or a metallic smell of wires melting (shorts in a system can be very dangerous, more so in a wet environment). Other strange burning/scortching smells, like hair or clothes should be an alert that something is wrong.

Taste: Taste is the final arbiter of what goes in and comes out of your system, ultimately resulting in a high quality rich brew. ALWAYS taste your water, even if using R/O. Taste your malts, they should be nutty and fresh. Taste along the way - the cooled samples for pH measurement. Taste for conversion into sweet wort. Taste and evaluate your hydrometer sample before pitching yeast. Taste your starter liquid (is it sour? should it taste like that?).

Of course, taste along the way through fermentation. Some people dislike the taste of yeast. I don't mind it - and learn a lot evaluating the change in the wort as it becomes beer. Both the flavor and aroma will transform throughout the process, and stability of both will also help you understand when it is ready to transfer (secondary, keg or bottle) for carbonation. Taste along the way during carbonation (harder with bottles) and determine what contribution CO2 is bringing to the beer - it may totally change the landscape.

Conclusion: While we tend to focus on the devices and tools we need for brewing, for thousands of years, beer, wine and mead have been made and consumed through the careful use of the brewer's senses and common wisdom. Sight, Sound, Touch, Smell and Taste are our front line tools to brewing well!