Building a Recipe: Saison

I am on a saison kick… maybe more like a saison obsession - they taste like summ and it has been cold this winter. I thought I might do some “rambling” and exploration here about saisons and water profiles, since there seems to be some confusion relative to what is traditionally used, and what the general guidelines and a recipe might be for more malt forward, spicy and hoppy beer. It is saison brewing season now - at least before modern temperature controls - as fermentation could be managed in the cooler weather or cold weather. I am sitting in a snow storm in southern Ohio as I write this!

In reading Farmhouse Ales, Markowski has a wonderful definition, which is to say, no real definition. He pushed the standard wide open with examples from all over Belgium and Wallonia. However there are some very specific points he makes:

- Saisons are very dry, usually with finishing gravities under 2° P, even with fuller bodied ales

- Saisons are spicy and fruity – driven primarily by yeast character

- Saisons are more hoppy than other Belgian styles, usually with low alpha hops, from local, nearby “noble” varietals or even with British hops.

- Saisons typically are colored from pale to orange

- Saisons generally have an earthy and rustic quality

This historic exploration of saisons revealed an even broader stylistic delta. These were very much “farmhouse” ales – and were produced seasonally to provide safe drinking and nutrition to farm workers. So where modern saisons have trended to higher alcohol levels – very low alcohol versions were served to keep workers on their feet, despite the months of storage.

While there is a distinction between Bière de Guarde and Saison, both were brewed “in season” and cooler weather to prevent spoilage, winter and spring, and stored to serve in summer months. Again, we should recognize that 3-4% alcohol by volume is adequate to facilitate such storage, rather than assume the more modern 6-9% levels would be required. The antiseptic qualities of hops were utilized, and saisons have been noted to be bitter, and often dry hopped in antique recipe research. Because these beers were aged, they were historically stored in wood, and would have developed a distinct yeast and microflora profile – specifically with brettanomyces and likely lactobacillus and pediococcus bacterium. These are farms and frugality is king – the fermentation vessels and storage would have been used over and over – and eventually producing a local yeast character.

Proof is in the glass however. In preparing for research, I find it useful to look at commercial styles, such as Saison Dupont, Fantome Saison or a more local Ommegang Hennepin. Here in Austin, Jester King brews wonderful farmhouse ales, such as Le Petite Prince (table ale) or Noble King (soured).

From a water management perspective, my goals would be to find a profile more or less similar to Dupont or Fantome, but thinking through what happens in the brewhouse.

Recipe Considerations

Markowski spends a good deal of time on the local water profiles. It seems that most of the water in Wallonia is moderately hard with enough residual alkalinity to require acidification. Specifically – he points to the following ion levels as typical for the region:

- pH 7.1

- Bicarb 350

- Ca 52

- Cl 20

- Mg 17

- Na 35

- SO4 107

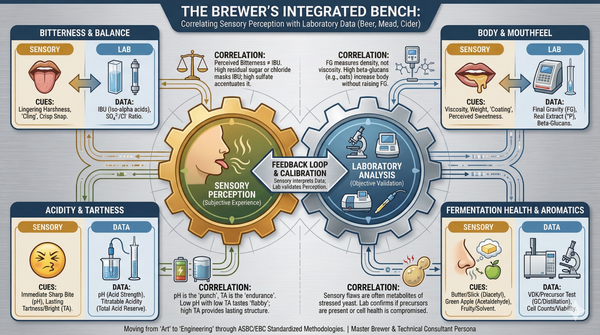

For ales that were not particularly dark or used roasts, the water seems fairly hard, albeit much lower than Burton ales. The sulfate should contribute to a rougher hop character and a dryer finish to the ale. However, it should be noted that 350 ppm bicarbonate is significant and would require acid to bring a pale grist to a reasonable mash pH. If we are not using acid producing microflora, then it maybe desireable to reduce the mash pH to 5.2 using acid or acidulated malts, and nudge the flavor profile in the finish beer.

If we look at various regional profiles in Bru’n Water, we can see ranging levels. The sulfate and chloride levels are variable, while sodium and magnesium levels are generally very low. In this instance, it may be useful to hone into a specific village or brewery and examine their treatments and ion profiles. Cross referencing breweries to regional profiles using Google maps is useful.

The Dupont Brewery is located in Tourpes, in West-Hainaut, Belgium. While a modern brewery, it remains a gold standard for saisons. The reference in Farmhouse Ales above, is from this region, but clearly not after the brewery treats the water for alkalinity. Nearby Brussels seems to have similar water with SO4 at 70 ppm and chloride at 41 ppm. We should assume the water is treated to bring the mash pH to optimal levels, but the hardness remains moderate.

We are then left with some choices, mostly relative to our source water and grist bill. While the Dupont water report maybe accurate, I have some concerns with over 100 ppm sulfate in a beer that uses noble hops. 100 ppm is not extreme, but I am not sure where the sulfate concentration will create harshness with these low alpha hops. In both reports, Ca is between 40 and 50 ppm, so seems a desired target and will help in the kettle. So I would shoot for something closer (if not right on) to the Brussels profile. The Ca levels may also create a clear product, or more accurately, less

I need to consider the use of spices. Farmhouse Ales seems split on the idea of spicing saisons. Farmhouses would most certainly use what was available, and there is evidence of adjunct and spice usage – though more in modern variations. Fruity esters with a medium to high spicy or floral aroma, and spices should balance but not dominate. Tartness and a mild sourness are acceptable – and moderately sulfate water is also mentioned by the BJCP 16C definition. This should be a heavy influence if I intend to submit to competitions and stay out of the Belgian Specialty Ale category.

In the next part, I will focus on the recipe and water profile.