Building a Recipe, Part 2: Saison

In the last post, Building a Recipe: Saison, I went through some of my thought processes and research in building a new recipe. Something I didn't cover was the source for a recipe, and that varies greatly. A great place to start is Brewing Classic Styles, Zymurgy or Brew Your Own magazine. You might also ask at a brewery or inquire someone in a home brewing club. Remember that the recipes need to be modified for your own system and efficiency.

I have brewed a lot of saisons, and developed my own house base saison recipe:

- 80% Continental Pilsener (2-Row if in a pinch)

- 9% Rye or Wheat (varies between malted and flaked)

- 5% Belgian Aromatic (Biscuit as an alternative)

- 1% Special B (for color)

- 5% Table Sugar or other sugar (in the fermenter)

You may wish to add 2-3% acidulated malt to manage pH, rather than using a liquid acid.

In this case, I want to feature Saaz and Tettnang hops, with a bittering charge from German Magnum or Northern Brewer to stay reasonably traditional. I will push a lot of late addition hops – looking for the spicy and floral characters, while restraining bitterness to under 30 IBUs. If I shift far from this general recipe, then I will run a 1 gallon test batch, or split batch to test variables. I should add that I really enjoy a strongly hopped saison – even with high alpha hops, however, not appropriate for competition.

Since part of the saison ethos is terroir, I am substituting Blacklands Malt 2-Row, which is malted nearby in Leander, Texas and will explore more regional adjuncts where possible. I also plan to take a more “frugal” approach, using what is on hand, appropriate with the farmhouse ethos, while managing the distinct flavors necessary to be competitive. That two-row is quite distinctive, but could use something to make it more “Pils-like”. Be aware you may need to up the 2-row as the extract yield from Blacklands maybe higher.

Here’s the recipe for 10.5 gallons:

[beerxml recipe=https://storage.ghost.io/c/c2/87/c2876a49-5c65-4965-946c-679dac007e84/content/files/2025/11/wallysorchardsaison-2.xml metric=false cache=-1]

I deviated from the house saison guidelines for a number of reasons:

- Pilsener is a premium malt. And I happen to have two bags of Blacklands 2-Row which has a fairly malty taste, much richer than normal 2-row. It’s an appropriate background for the fruity and phenolic saison yeast. White wheat will add another layer of flavor.

- Aromatic – really a light bit of insurance on making sure there is enough malty backbone to lift the two row – both in flavor and in aroma. I also like the little bit of color it brings.

- CaraPils will add a little body with dextrins. I use very little however – and find this works well for foam stability.

- The orange juice and zest, and the Seville Orange Peel lift the fruity character slightly – without turning this into an orange soda. The zest really brings more of an herbal sense. Will also spice the finished beer with a tea after it is carbed, but only if needed.

- Mixing Tettnanger and Saaz really allows me to complex both spicy and floral flavors and aromas, which I feel is critical in a saison. I am trying to nail down the right dry hop, and may lean toward a more citrus hop than a traditional, as a background supporting character. Depending on the myrcene levels of the hops, I will adjust up or down in volume.

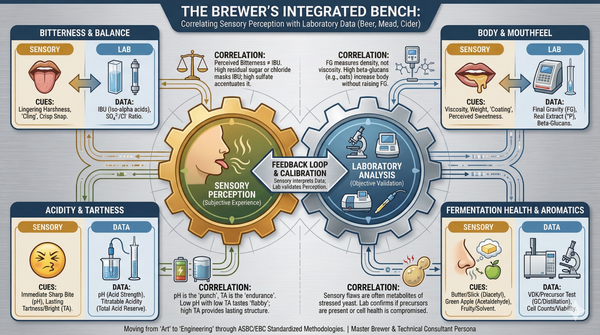

Water Additions for R/O

Matched sulfate and chloride levels for the “Brussels (boiled)” profile in Bru’n Water

To mash water – added 3.8 g of gypsum and 2.3 grams of calcium chloride

To sparge water – added 3.3 g of gypsum and 2.0 g of calcium chloride

It seems like a lot of work to come up with just that tiny addition (relative to an American IPA profile) and a bit circular when I could have just gone straight to the spreadsheet. The research and critical thinking should come through in the glass. I wanted a fairly accurate saison beer, just slightly tilted to an orange aroma and flavor, but with depth in of subtle phenols, spices, herbs and malts.

Mash Regimen

I find that saisons should be thinner but not watery, however, BJCP declares light to medium body. High alcohol versions will naturally have a thinner finish. The primary mash target should be somewhere between 152F and 154F, and I will normally do a short rest at 133F to help with the wheat. In this recipe, it is not required, but the time spent ramping from 133F to 154F will help the fermentability of the wort. A 60 minute rest at 154F, with a 10 minute mash out at 170F, and sparge at 170F.

I sparge at 170F but with sparge pH capped at 5.8 pH. This prevents tannin extraction, and allows for a very smooth and easy lauter.

I brewed this recipe about three weeks ago, and kegged just before I left for Ohio. When I return, I should be able to take some pictures and sample the carbonated beer. The uncarbonated sample was very nice... restrained phenolics, a very subtle fruity character with a hint of orange.

Yeast Choices

A quick note about yeast. While I tend to use dry yeasts, saison maybe the right place to experiment with choices from Wyeast and White Labs. Look for "saison" in the name however... these yeasts are responsible for nearly all of the flavor profile. There is a lot of variation - from spice forward to fruit forward profiles, and more specifically attenuation. Saisons should be dry - and for me, bone dry. Expect a finished gravity below 1.008, sometimes even below 1.000. Carefully read and study about the yeast strain... some, like from Dupont, are terribly finicky and require special measures to ensure a complete fermentation. Don't expect a completely clear beer, some cloudiness can be expected, but I find that extended lagering (especially when using irish moss) drops a good amount of the yeast - resulting in a beautiful beer.

I find that pitching rates and temperature also shape the final profile. Cooler fermentation creates a cleaner flavor, where hotter fermentation intensifies the phenols and fruitiness. While people seem to believe that underpitching cell counts increase the phenolic flavor - the risk of a failed fermentation is too large.

I chose Belle Saison for this beer, as it finishes very dry, and I had a slurry from a 1 gallon test batch in the refrigerator.