Blacklands Malt - local, small batch maltster

Small, local malting companies are springing up all over the US. A few years ago, it seemed a small scale malting trend centered around larger nano- & micro-brewery centers, both east, west and north, but not much in the middle. It was a matter of time before one came to Austin, and surprisingly, Blacklands Malt is the only maltster of any size in all of Texas!

The idea of brewing with local ingredients is an important concept and is tied to the history of brewing. Today, the best a brewery can hope is to use all US grown products, challenging with today's international agriculture market. It seems, at least here near Austin, we will soon have locally grown and malted barley and wheat malts. That is a great thing!

Blacklands Malt opened up in Leander, Texas, north of Austin, and delivered their first commercial batch to Jester King Brewery in December, 2013. Despite the relatively quiet market entrance, a note went out to Zealots members that home brewers could buy malt by the bag, and get a cool little tour. I have had the chance to brew with Blacklands’ Pale Moon™ North American 2 Row Base malt – and been thrilled with the quality and flavor. Because I am working on a new large barrel project (to be covered later), I have purchased more bags of 2 Row and White Horn™ Pilsner.

Home brewers must go to the facility to purchase bags – they are not available on the internet or in a shop. Call ahead as volume may be limited. Their malt is very popular with local breweries!

Blacklands Malt is named after the Blacklands grassland eco-region (prairie) of Texas that extends from north of Dallas down to San Antonio. Brandon Ade and his wife Samantha, own and operate the business, along with Riker (yes, a Star Trek Next Generation reference and very handsome dog) who demands playtime to keep things interesting. Brandon is a Texan, born in Killeen, and grew up in Indiana, graduating from Purdue University with a BS in Computer Engineering. He moved to Austin in 2005 for a career in semiconductor. Samantha is a New Mexico native and moved to Austin to get her degree in law at UT. They met playing co-ed dodge ball in 2008, and married. A passion for home brewing and craft beer inspired them to leap into becoming Texas' first and only malting company.

NOTE: I am not a journalist. So if the following seems amateur... :)

I asked Brandon a few questions:

We are all familiar with nano- and micro-breweries. With your craft malting business, would you consider yourself a micro-maltster (what is the formal job title)? What size batches do you produce? What is the basic process?

[BA] My formal title is "Maltster". Whether you consider me micro-, craft-, or otherwise is an exercise in semantics. I like to describe ourselves simply as a "small malthouse". When you compare our batch size of 2 tons against the large industrial malthouses with batch sizes of 600 tons, small seems to be the best descriptor for what we do. The basic process of malting is steeping, germination, and kilning. You can get an overview at Malting 101

Right now, you have to import raw barley into Texas and malt in your facility. How soon do you think we can purchase Texas grown barley and wheat malt? Any plans for certified organic malts?

[BA] I am currently (3/18) malting a batch of Red Winter Wheat that was grown right here in Central Texas! This will be the first locally grown and locally malted grain in Texas history. Funny that it turns out to be wheat instead of barley. Our first Texas grown barley crop will be harvested in May and the first malts from this will be available in June/July. No plans for organic certification at this time. Most of the farms I work with use organic practices without the label, and I prefer knowing that, much more than having a label say it.

It seems appropriate that you are located on an “old farm to market” road. How do you see the current “Farm to Table” and “Eat Local” consumer values impacting your business?

[BA] I think the movement of eating locally produced foods is a sign that people crave the connection with agriculture again that has been lost over the years. This positively impacts my business because many breweries espouse to support local ingredients and local business and you can't really claim to do that without showing support for local producers. The increasing consumer demand for local products also drives the market and gives a tangible lucrative business reason for brewers and maltsters to support and develop local agriculture. My goal is to connect the farmer to the brewer to the consumer so that at the end of the day a customer can have a beer in Texas and know everyone who was involved in making that beer. What a beautiful sight that would be.

Do you have a goal that defines “local”? All of Texas or Hill Country?

[BA] I define "local" as the furthest I can drive in a day without complaining about it.

It is easy to forget how beer, particularly malt and hops are agricultural products. How are you connecting the beer drinker to the land? If there is a Texas “terroir” - what do you thing it maybe?

[BA] The brewers have all the glory in connecting with people when they enjoy their beer. And it is the responsibility and honor of the brewer to make good beer. All I can do is make the best malt I can and give the brewer that one good ingredient to work with. So while I continue to educate and shed light on what local malting is all about, and show people where their grains could be coming from, unfortunately malting is a faceless industry that does not get a lot of public attention. So I ask, "Where does your malt come from?". And I hope that question sparks a thought and a conversation with people when they really think about it. Do you know from where your last bag of Great Western, Rahr, Weyermann's, or Simpson's malt really comes? Do you know how long it had been in storage before you bought it? Do you know where do go to even find out the answer to those questions? All those things you can find out by asking your local maltsters, and that's how I'm trying to connect people to their agriculture.

You currently produce an under-modified Pilsner malt, a well modified 2-Row and a light crystal malt. Are there plans for other malts or un-malted products?

[BA] If I stopped at base malts I wouldn't be much of a maltster. Yes I absolutely plan to add to the list but it will be a matter of time. Right now I'm producing the White Horn Pilsner, the Pale Moon 2-row, a soon to be Red Winter Wheat, and I also offer Raw Red Winter wheat now as well. The Cold Rock crystal malt has been put on hold until the Summer time. My next variety outside of those will likely be a Munich, Brown, or dark crystal malt. Time will tell.

In the world of scorching IPAs and super hoppy pale ales, can craft malts stand out and make a difference in brewing?

[BA] Only brewers and the consumer can answer that. Do you care about local production, local foods? Do you think there is an appealing marketing story to tell by growing local grain and malting it? Everyone has their own opinion about what is important and what they believe in. Malting has been around for 1000's of years. I'm not reinventing the wheel in what I do. But if you think local malting is something important to you then it will make a difference to you drinking a beer and knowing where it came from. Personally, I think the production of local ingredients is the next great leap forward in brewing in North America and local malting will be a big part of that story.

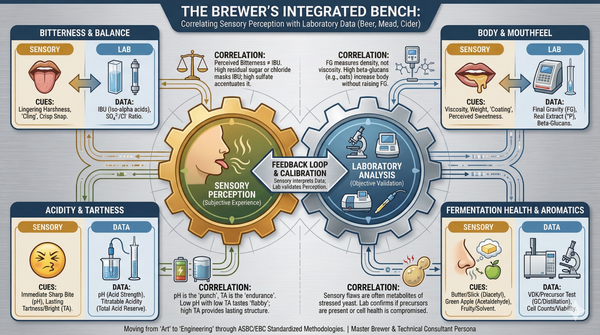

You provide extensive data on your malt analysis sheet. What characteristics are most important to a home brewer? What are the quality characteristics you strive to differentiate your product from the big maltsters?

[BA] Why do 100 different malt varieties and 100 different maltsters making them exist around the world? Because everyone cares about different things. I can't tell you what is most important on a spec sheet because every brewer looks at different specs and picks out what they consider important. What I do is make a great malt and give you the brewer as much information as humanly possible to make educated decisions. What you do with that data is your choice.

While there is definitely competition between brewers, there is also a strong supportive culture. I saw the same growing up in northern Kansas between farming families - is there a similar culture between craft maltsters?

[BA] Yes and no. The small maltsters around North America that are doing the same thing I am doing, have come together first as an informal group, exchanging emails and phone calls, and now as the formal Craft Maltsters Guild. It's a way to share ideas, grow our expertise, and collaborate. As you can imagine in the early days there are a lot of ideas flying around and we continue to hash them out as we go. On the flip side of this though is a very real reluctance by some to share too much data on things such as recipes, equipment, etc... You can imagine that if you are a pioneer in this field and have spent months or years figuring out techniques through trial and error, research, and the school of hard knocks that you would be reluctant to just give that knowledge away. And you can imagine your reluctance if you suddenly have other would-be maltsters popping up in your backyard. So there is a wide mix of where people stand on sharing information. I will say this, no matter who you are, with small malting being so new, all of us are constantly figuring out things as we go.

You ordered a custom kiln which is a thing of beauty! How much personal engineering went into the design and what are the advantages of this kiln versus a more traditional raked system? How would your process compare to floor malting?

[BA] I still have the original engineering graph paper that I drew my original design on. That should give you a very real sense of how much personal engineering I had to do. It took over a year of design work.

The advantages of my system are tight process control through metering capability and automation, as well as having 100% stainless allows for easy cleaning and durability. The disadvantages are that it still requires much manual labor including turning the malt. It is similar to floor malting in that I must turn the malt by hand but it is different in that I do it in a bed 3' deep and must "dig" my way through the malt versus floor malting that has a thin bed spread over concrete. If I could afford it I would have installed a motored turning system, but alas you build what you can afford.

Your business is very much brand new, conceived only about a year ago. What has been your favorite moment so far? Any crazy scary moments?

[BA] Every day is a scary moment in the life of a new business owner. I'm constantly dealing with new problems.

My favorite moments so far have been receiving and installing the newly built equipment back in September 2013, drinking the first few beers made with my malt (Pinthouse Pizza, Blackstar Coop, Hops & Grain), receiving the 2013 Austin Food and Wine Alliance Grant, and the tours I gave during the last MBAA conference in town because it was right before the malthouse went into first production and everything was clean, shiny, and ready to make malt!

You currently sell in bulk and bag commercially and in bags to local home brewers. Any plans to sell directly via the internet or through home-brew shops?

[BA] No plans right now. Until home brewers stop making the trip to the malthouse I don't have a reason to sell online. You can visit the only malthouse in Texas and pick up local malt direct from the source for $1.10/lb. That seems to keep people coming back.

Do you home-brew anymore? If so - what is your go to style or recipe?

[BA] Sadly no. I'm too busy these days to brew. My favorite beer I made back in the day was a robust vanilla porter using real vanilla beans. It came out at around 6.5-7% and had more of a roasted chocolate character to it with just a little sweetness. I used to drink a liter of that after work every day when I had it on tap. Yum...

So I have found a new malt source. One that is local and I can talk directly to the guy that turned out the product! Compared to a bulk buy scenario from Great Western or Rahr, Blacklands is a premium price, but compared to the "by the pound" prices at my LHBS, I save money. Knowing when and where my malt was processed, and that I am buying fat and fresh malt grains, I am quite happy. Hopefully, this will prove out in competitions. I also pay a lot more attention to where my malts (even specialty malts) come from and how they wind up in my kettle.

In a future post - I plan to discuss reading a malt bill and what the more important tests represent, using the reports from Blacklands.